Inside the World of Private Museums

Once typecast as places that housed historical relics, museums have been subject to an overhaul since the last millennia, with a new wave of collections that have shifted the art world’s centre of gravity.

Although not a new concept, the private museum model has seen explosive growth over the past 20 years, and Europe is at its core. Home to the largest number of private museums globally, Europe accounts for 45% of all global collections.

Usually a result of individual whim, these collections are often eclectic as is the by-product of one collector’s taste, which, owing to the absence of curators or art advisers, can head in odd directions artistically. However, this is the essence of their charm. Their uniqueness. Their ability to place an intrepid footprint away from the tourist routes of the art world.

Standing for what is avant-garde and international, these private collections possess a sense of hedonistic individualism over what has traditionally been perhaps perceived as archaic, stagnant, and domestic.

Let’s not forget that the Tate and the British Museum in London were based on private collections. The founding collection of London’s National Gallery belonged to a banker, John Julius Angerstein. And Peggy Guggenheim’s collection has spanned decades.

Guggenheim

An avid collector of art, US-born Peggy Guggenheim started collecting art in her 40s but had a deep interest in art from her 20s, when she travelled around Europe. “I soon knew where every painting in Europe could be found,” she wrote in her autobiography, “and I managed to get there, even if I had to spend hours going to a little country town to see only one.”

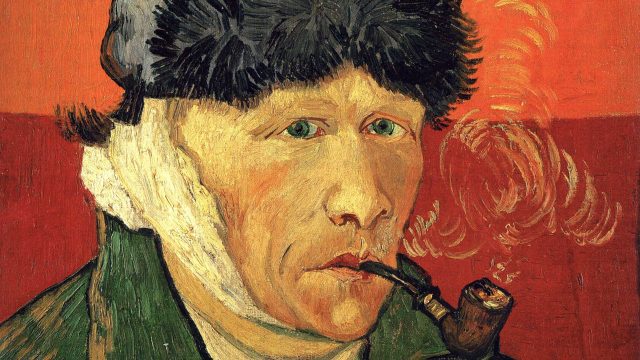

Photo: Man Ray, courtesy private collection.

© 2017 Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2017

She collected art in a way that was entirely enveloped in passion – picking up items that didn’t sell and works for which there was, as yet, no market. She bought art, not as an investment but because she had an eye for something that she perceived as great. The society heiress was gradually transformed into the European art world’s boho queen and set up the Guggenheim Jeune gallery in 1938, with 30 drawings by Jean Cocteau. Her gallery grew, and she gave Wassily Kandinsky his first-ever London show, then an exhibition of contemporary sculpture featuring artworks of Henry Moore, Hans Arp, Brancusi, Alexander Calder and Anton Pevsner.

After a year or so, when the gallery in London failed, and the world became ravaged by war, Peggy invested $40,000 in a collection of paintings by Picasso and Max Ernst as well as artworks by Joan Miro, Rene Magritte, Salvador Dali, Paul Klee and Marc Chagall.

After the war she moved to Venice in the 1940s, acquiring the 18th century Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in Dorsoduro along Canal Grande – where she installed her art collection. From 1951, she opened her house and collection to the general public every summer and continued to add to her collection over the next 30 years. In 1976, three years before her death, she donated her palazzo and art collection to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation of New York, and her home has since been open to the public as a major tourist attraction in Venice with around 400,000 visitors a year.

At the completely opposite end of the spectrum are purpose-built private museums which are often housed in architectural masterpieces of their own right.

The Kistefos Museum

The Kistefos Museum in Norway is one such example. Located on the site of a wood pulp mill built in the 1800s, the museum consists of an array of industrial buildings around which the Kistefos Sculpture Park was created in the late 90s. Featuring 45 sculptures created by prominent artists such as Yayoi Kusama and Anish Kappor, the park has evolved over the years with a range of large, contemporary, and site-commissioned installations which juxtapose beautifully with the industrial heritage of mill and surrounding buildings.

Photo: Knut Arne Breibrenna

More recently, in 2019, a unique ‘twisted’ building which is dramatically torqued at its centre, was built to connect the two forested river banks which site the industrial museum and the sculpture park. In an impressive display of contemporary architecture designed by BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group, the museum opened in 2019 courtesy of Christen Sveaas, a businessman and art collector who spent much of his time curating a personal collection of contemporary artworks.

Sveaas’ aim was to create an awe-inspiring contemporary art museum which complimented its surrounding cultural heritage. In an interview by Georgina Adam from the Financial Times, Sveaas stated “any rich man can build a sculpture park anywhere in the world; no one but me can build one around an intact 1889 factory”.

Kistefos holds two art galleries that play host to new art exhibitions every year, featuring highly recognised national and international artists, and a museum which was listed as one of ten technical and industrial cultural heritage sites in the country, acting as a modern, industrial monument worth preserving as part of Norwegian and Scandinavian culture.

Julia Stoschek Collection

Then there are the wealthy billionaire heiresses such as Julia Stoschek. The Julia Stoschek Collection is an international private collection of contemporary art with a focus on time-based media, rooted in artists’ moving image experiments. Consisting of photography, sculpture and painting, the collection, which boasts over 860 artworks by 282 artists from around the world, also spans video, film and moving image installation, multimedia environments, sound, and even virtual reality.

Unique in its heterogeneity, Julia Stoscheck’s collection is representative of her emotional investment in the subject matter – fascinated by video, her approach for art collecting involves deep research into art history and following an artist over many years to build up a more complete picture of their creative journey.

Julia opened her first museum in Düsseldorf in 2007, firstly because her collection outgrew her apartment but secondly because she wanted to make it available to the public. Located inside a modernist-style building from 1907, the historic structure includes the Julia Stoschek Collection and her apartment within it.

Foto: © Ulrich Schwarz, Berlin.

In 2016, the Julia Stoschek Collection opened a satellite exhibition space in Berlin, which gathers more than 750 artworks by European and US artists. However, it was announced last year that the Berlin location might be forced to close in 2022 owing to pressure from the real estate industry. With a significant hike in rent for the building that occupies the collection, and a refusal to sell the building to Julia, the collection is at risk of shutting down if an alternative site cannot be sourced.

This is one of the major challenges of private collections – while some private museums create a lasting legacy in their own right, many are said to rarely outlive their collector. Unprotected by government institutions, organisations and bodies, and often less revered by members of the public in the same way that public museums are, the threat facing private collections is often very real.

In the cold, harsh environment of business and commerce, the cultural core of art’s purpose is often lost to the pursuit of wealth. With private collections rarely protected by anybody other than the collector themselves, it’s a concerning affair when a collector passes away. Some have stood the test of time, but many have also been sold off to other collections or have simply dispersed via private auction.

But despite the open risks that private museums face, the fact that they exist is something to revel in. Embodying a different approach to the way we experience art, the quirks, idiosyncrasies, and the deeply personal imprint of a collector’s agglomeration is what makes them unique. And long must they live.