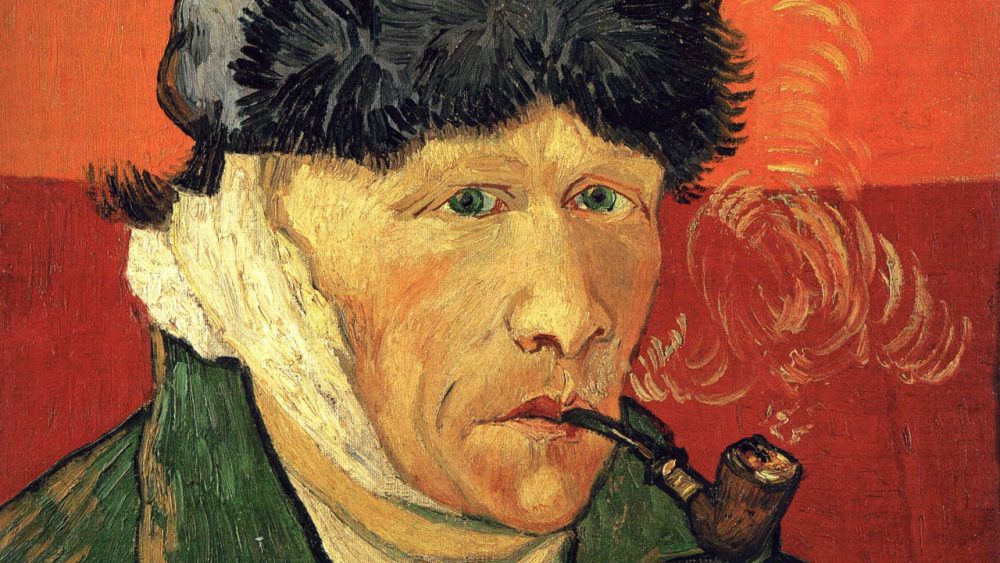

Self-portrait with bandaged ear and pipe (1889), Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Wikimedia Commons

Mad Artist: The Correlation between Madness and Genius

The one who chopped off his ear, his art is recognized worldwide. But even if people knew nothing else about Van Gogh, they will likely know this gruesome, strangely compelling fact. The reality is that Van Gogh suffered from a mental health disorder, experiencing multiple breakdowns, and ultimately committing suicide. Van Gogh has become the symbol for the myth of the mad artist, fueling a somewhat romantic fiction of artists as tortured geniuses, whose madness is often exaggerated or inaccurately represented.

I am unable to describe exactly what is the matter with me. Now and then there are horrible fits of anxiety, apparently without cause, or otherwise a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the head… At times I have attacks of melancholy and of atrocious remorse.

Van Gogh to his brother before his suicide

Some attribute the birth of this ‘mad artist’ myth to Aristotle. This may be the origin of the perceived linkage between madness and genius. For thousands of years, creatives, scientists and psychologists have been trying to get to the bottom of whether there is, in fact, a correlation between mental health disorders and creativity.

No great genius has ever existed without a strain of madness.

Aristotle

A 2015 study in Iceland found that people in creative professions were 25% more likely to carry gene variants that increase the risk of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. A Swedish study, which tried to establish whether creativity is linked to all psychiatric diagnoses (particularly in authors), found “an association between creative professions and first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anorexia nervosa, and for siblings of patients with autism”. A recent report shows that 73% of musicians have suffered from mental illness, and a report from the Office of National Statistics in England for 2011 to 2015 indicated that those working in arts-related jobs were at high risk of suicide (in some cases up to four times more at risk). Other papers have suggested a link between bipolar disorder and creativity, assessed mood disorders in British writers and artists, and psychoanalysed women artists compulsions to create.

Louise Bourgeois

© Christopher Burke

Source: FT.com

While these findings may seem compelling, the studies are certainly not without their critics. One persistent issue is the degree of the correlation found, with many arguing that the evidence is negligible and not unequivocally indicative of any cause and effect relationship. The other major flaw is how ‘creativity is defined in the studies. How does one identify and quantify ‘creativity’? Albert Rothenberg (Harvard University) is one critic who feels there is insufficient evidence to confirm a link.

It’s the romantic notion of the 19th century, that the artist is the struggler, aberrant from society, and wrestling with inner demons. But take Van Gogh. He just happened to be mentally ill as well as creative. For me, the reverse is more interesting: creative people are generally not mentally ill, but they use thought processes that are of course creative and different.

Albert Rothenberg

Literature on the topic has swung both ways. Albert Rothenberg’s book investigated 45 Nobel laureates and found no links between creativity and mental illness. Kay Redfield Jamison’s book presents biological foundations for artists she postulates suffered from manic-depression, and she discusses the correlation between their bipolar disorders and their artistic temperaments.

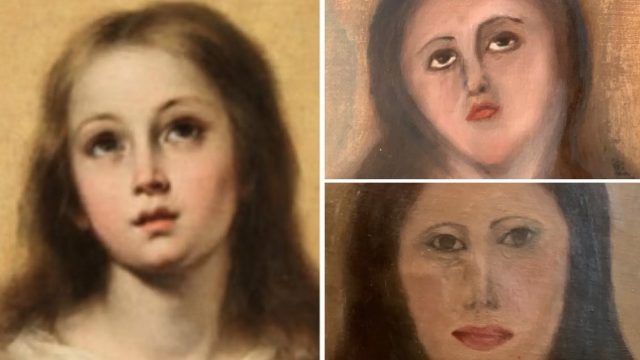

Egon Schiele (1890–1918)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Aside from Van Gogh, Egon Schiele’s self-portraits depict an emotionally raw and tormented figure (although recent research suggests he may have drawn on studies at mental health facilities as source material). Edvard Munch’s The Scream apparently came to him in a vision, and he suffered from various unidentified mental illnesses throughout his life. In his words:

My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness,’ he once wrote. ‘Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder… My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art.

Egon Schiele

The lifestyle patterns among artists may be strong contributing factors as well. Artists are typically self-employed. Their income can be sporadic or low wage, often leading to financial insecurity. Without working hours set by an employer, there can be a pressure to work all the time – leading to poor work-life balance. The poor work-life balance can negatively affect social interactions, sleep patterns and anxiety levels, all potential drivers for depression and substance abuse and dependence. For many artists, continually assessing and reassessing their work is stressful and taxing, and the inevitable criticisms can have a significant bearing on success. Like sportspeople, musicians or chefs, their output is constantly assessed for whether it’s “good”, and nobody can be good all the time.

Another consideration surrounds visibility. Does the perception of a linkage between mental health problems and artists come from the simple fact that artists are just better than the rest of us at revealing their emotional struggles by using art as an outlet to express their inner feelings, tribulations, doubts, and wishes?

Agnes Martin (1912-2004)

© 2018 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Source: Guggenheim

Agnes Martin was a diagnosed paranoid schizophrenic, suffering from auditory hallucinations, depression and trances. She had several severe episodes, beginning in the 1960s. She was hospitalised at various points in her life, treated with electroconvulsive shock therapy, and participated in therapy sessions to manage her symptoms from 1985-2000. Ultimately, her paranoia led to extreme restrictions and fraught relationships; consequently, she lived a fairly solitary life. The more you read about her mental health, the more her precise, orderly, and rigid works make sense. In 1933, Georgia O’Keeffe was hospitalised for psycho-neurosis. Louise Bourgeois suffered from depression and attended psychoanalysis four times a week for nearly 60 years.

There are certainly examples of famous artists who have had intense struggles with mental health throughout their lifetimes and careers. While we may not ever get to the bottom of whether there is truly a correlation between mental health disorders and creativity, we can observe how these illnesses manifested in specific artist’s creative output.

The research on the linkage between mental health disorders and creative ability will likely continue for some time, as the findings that exist are neither straightforward nor conclusive. Fortunately, the stigma around mental health issues has lessened since Van Gogh’s time, and there are more resources available to anyone suffering, artist or otherwise, than ever before.