Art restorers train for years to hone their craft, in order to best mend, treat and provide preventive care for invaluable works of art. Generally, they will specialise in one area: sculpture, works on paper, paintings, ceramics or furniture, for example. Either through higher education or apprenticeships, they gain the skills and expertise to assess the condition of an artwork and provide treatment options that will ensure the work remains in the best possible condition, both now and in the future.

The Courtauld has an MA in the Conservation of Oil Paintings, as does the Hamilton Kerr Institute (part of the Fitzwilliam, Cambridge), and Northumbria University. Cardiff University, City and Guilds London Art School, Durham University, University College London, University of Lincoln, University of Glasgow, University of York and West Dean College of Arts and Conservation all have courses covering some aspects of conservation or restoration, not limited to oil paintings.

In the UK, apprenticeships are offered in two areas: a Cultural Heritage Conservation Technician Apprenticeship or a Cultural Heritage Conservator Apprenticeship and are available to all aged 16 or older. The minimum term is one year, and the training consists of both employment and off-the-job learning and development.

Icon, the Institute of Conservation, published an interesting article with input from conservators in various fields, offering tips on 10 traits you need to succeed as a conservator. From craft and communication skills to patience and business acumen, it is clear that being a conservator is a demanding, technical and challenging career choice. Icon quips in their article:

Those outside the field would be forgiven for thinking it involves fiddling with something for a very long time to sort-of make it look like what it did before.’ The object of a successful conservation or restoration is often an invisible repair. But what happens when a conservator monumentally fails on this front, or worse, what happens when an amateur takes on conservation? The selection of examples following show the importance of vetting a conservator, and of hiring a professional. Otherwise, the results can be devastating for cultural heritage, albeit somewhat comical.

Santa Bárbara in the Chapel of Santa Cruz da Barra

Photo via Twitter.

A 19th-century statue of Santa Barbara was widely ridiculed in Brazil after a restorer left her looking more like a Barbie doll than a saintly icon. While the thinly painted eyebrows, overzealously applied eyeliner and bright lips are distracting, it is the uniformly-applied, several-shades-too-light foundation, with no depth of colour, that leaves the statue looking eerie and doll-like.

St. George, Church of San Miguel de Estella in Navarre

Photo via Twitter

This case provides excellent evidence for why you should not simply accept a job because you have been offered it. In this instance, a conservator wasn’t even hired; instead, a local art teacher took on the job of ‘restoring’ this 500-year-old statue. The result looks more akin to a cartoon than a historic work of art, and earned him the nickname Tintin St George. After an additional $37,000 was spent to fix the restoration, St. George received the specialist attention he should have received in the first instance. The lesson: cutting costs and corners in conservation can lead to additional damage (sometimes irreversible) and additional cost.

Buddhist frescoes, Yunjie Temple in Chaoyang

Photo via Twitter

Spending vast sums of money on a restoration also does not ensure a good job, as exemplified by this restoration on a fresco from c 907–1125. Here, despite spending £100,000, the result looks more like a still from an animated film than a surviving fresco from the Qing dynasty. It begs the question how one could think there is more value in the image on the right than the image on the left. Many would say the end result is a new work of art entirely, given how little resemblance it bears to the original.

Sculptural Trinity of Mary, Saint Anne, and baby Jesus in Ranadoiro

Photo via Twitter

In this instance, a professional wasn’t deemed necessary at all, resulting in this 15th century trinity being gussied up by a member of the local town. The ‘restorer’ clearly felt that the traditionally unpainted trinity deserved some color, applying it in the extreme with industrial enamel paint. The outcome is appalling – with one figure looking like she is wearing a judge’s wig and the other looking like a Pez dispenser.

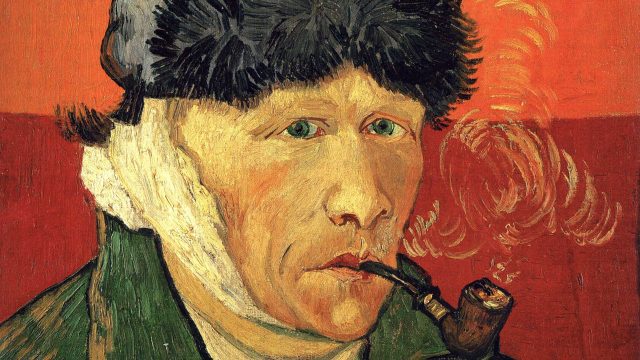

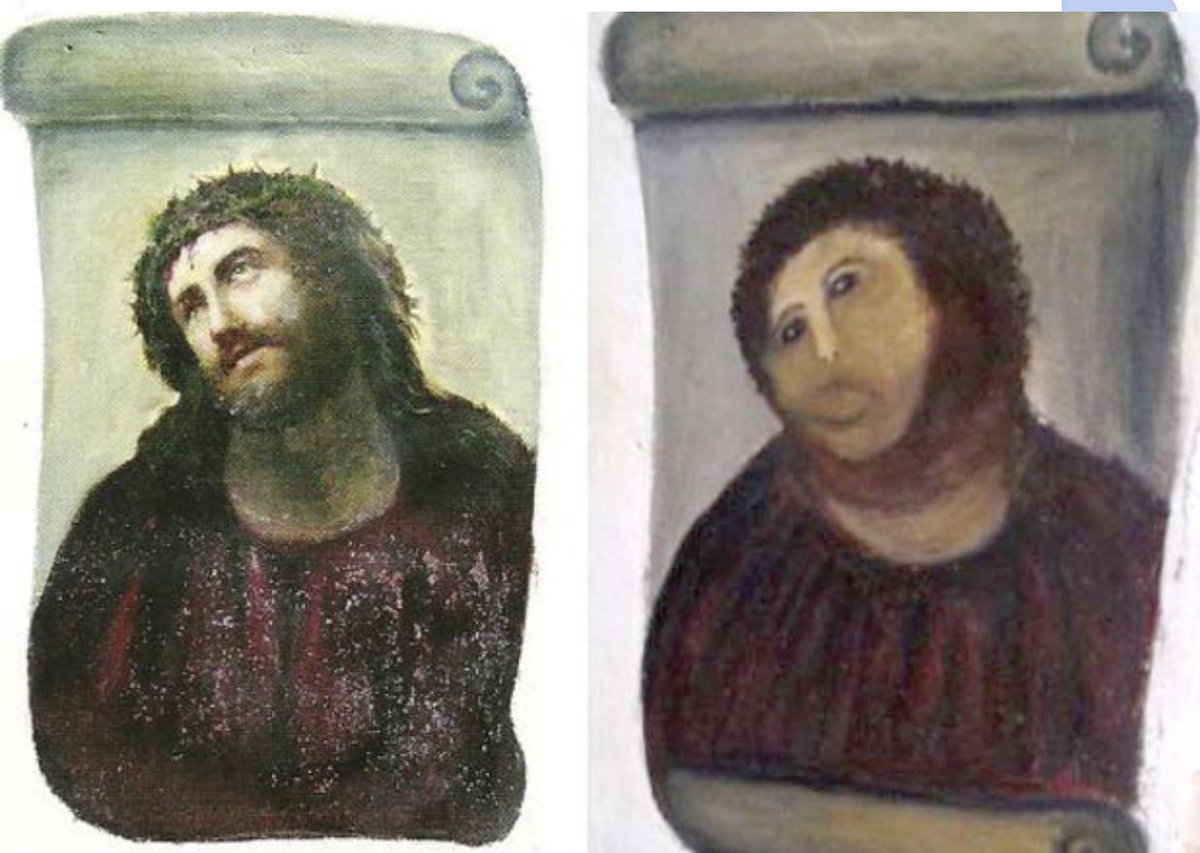

Ecce Homo in Borja

Photo via Twitter

By far the worst restoration example has to be the somewhat infamous Ecce Homo, now alternatively known as Monkey Christ, Monkey Jesus or Ecce Mono. This work was undertaken unsolicited (initially it was thought to be vandalism rather than restoration) by an 82-year-old parishioner of the church. The result, clearly more closely resembling a monkey than a traditional representation of Christ, has actually served the town well; as 150,000 tourists have come to the town purely to see Cecilia Giménez’s handiwork. This was not a restoration success, but perhaps it was an unforeseen blessing for a town with dwindling funds.

Immaculate Conception in Valencia

Photo via Twitter

In a worrying trend for Spain, this is the next unfortunate contender for the restoration disaster hall of fame. Unfortunately, during what should have been a straightforward clean, Mary seems to have transitioned several times, losing all resemblance to her original state. The result would no doubt be an admirable painting attempt by a child, but certainly not by a restorer.

9 de la calle Mayor in Palencia

Photo via Twitter

Photo via Twitter

In this example, a Spanish restorer demonstrated that restoration disasters are also possible in stone. Somewhat unbelievably, this still anonymous stonecarver must have thought this was a sufficiently good likeness to put it up and draw a line under the job. That, or he felt the spirit of Picasso come over him whilst carving. The result has been fondly nicknamed The Potato Head of Palencia.