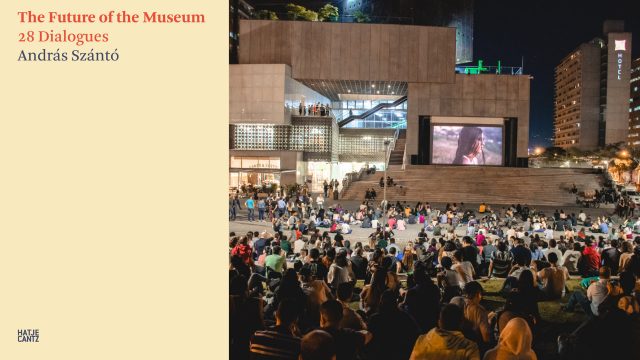

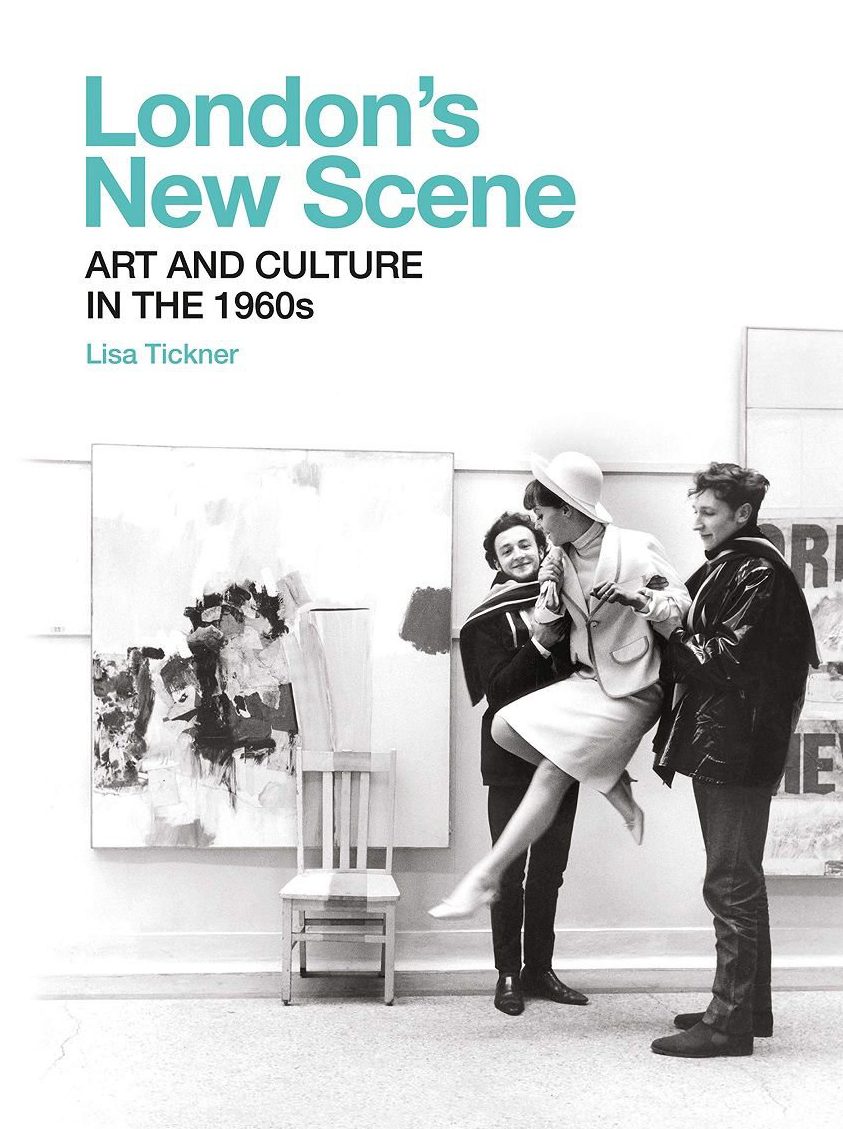

I started to worry that these book reviews would be almost exclusively complementary and lacking in criticism because I have enjoyed most of the books I have reviewed lately. I have to confess that I started reading London’s New Art Scene by Lisa Tickner, thinking it would be the book I would be most drawn to. In fact, I struggled through this book for nearly two months. I hoped that perhaps the next chapter would draw me in, or perhaps the one after that, but sadly, it never did.

Let me qualify my lack of enthusiasm by saying that sitting down with this book and reading it cover to cover may not be the best way to absorb it. London’s New Art Scene would have been an invaluable resource if I had been writing a dissertation or doing research to write an essay for a catalogue. It is also extremely well illustrated, which I find increasingly unusual. It is tricky to pinpoint what this book lacks, but I think it is the author’s voice. It reads like a textbook: chock-full of information, packed with references, but bereft of passages where the author engages with the reader outside of the facts presented. I cannot fault the writing as the book is well-written, easy to consume and straightforward. It is just not particularly captivating.

The book focuses on the London art scene in the 1960s, divided into seven chapters:

- 1962 – Pop Goes the Easel

- 1963 – The Kasmin Gallery

- 1964 – A Big Year in Modern Art

- 1965 – Private View

- 1966 – Antonioni’s Blow-Up

- 1967 – Export Britain

- 1968 – Art School Revolution

Tickner acknowledges that a lot has been written on this period already, and she succinctly states the aim of the text in her preface:

The aim is to contribute to a richer understanding of how particular artists and institutions negotiated the shifting currents of economic boom and recession, new forms of state and corporate patronage, an expanding visual field extending to design, photography, television and film, and by the end of the decade a wave of disillusion and political unrest.

The author feels there is “little in the published literature concerned with art patronage, art education, influential galleries and the market, significant public exhibitions and the new prominence of art and artists in the media”. Clearly, the author has done her due diligence in reading the extant literature and finding a gap she can fill with this publication. With 100 pages of notes, she has been attentive in incorporating those resources into this text. To try and summarise this text would be impossible. Instead, I will focus on a few of the chapters I found most interesting.

Tickner discusses, in careful detail, Ken Russell’s Pop Goes the Easel, a film made for BBC’s Monitor programme about Pop Art through dramatised (and in some cases exaggerated) depictions of the lives of Peter Blake, Derek Boshier, Pauline Boty and Peter Phillips. He approached David Hockney, who turned him down, and Patrick Hughes was keen to be included, but Russell turned him down. Tickner walks the reader through the film, portraying its scenes, describing its production, and chronicling the critical reception.

She provides an admirably succinct and straightforward definition of pop as “a new form of realism responsive to the experience of contemporary life as mediated through the visual rhetorics of mass culture”. Her profiles on the artists are engaging, but the most interesting for me was her survey on Boty. I will admit my lack of familiarity with Boty previously. Still, I was struck by Tickner’s description of Boty’s work as being feminist and celebrating women’s rights to sexual pleasure through images of women as sex objects.

The chapter on the Kasmin Gallery was very insightful. I agree with the author that not enough is written about how individual galleries have shaped and changed the art world. Tickner paints a picture of the Kasmin Gallery as a space that was much more than a gallery. It was a gathering space that attracted a particular set. Kasmin’s gallery concept established the groundwork for the “white cube” galleries that we know today: large, white, cool, well-lit gallery spaces with a roster of exclusively represented artists.

His transformation of the gallery space from the traditional country house or shop front model was revolutionary. The array of artists Kasmin represented is impressive: Hockney, Latham, Richard Smith, Bernard Cohen, Caro, Denny, Ayres, William Tucker, Howard Hodgkin, Kenneth Noland, Morris Louis, Helen Frankenthaler, Frank Stella, Jules Olitski and Larry Poons.

Kasmin became a major triumph, and the gallery’s artists achieved commercial success and representation in museum shows both in the US and the UK. Perhaps the gallery’s influence is best summarised by Kasmin himself when he wrote to Frankenthaler in 1965:

Everything is really swinging. We are all becoming celebrities and I have just been appointed art consultant to Vogue.

John Kasmin to Frankenthaler

At the 1966 Venice Biennale, Kasmin represented four of the five British pavilion artists and two Americans – an impressive feat for a gallery then or now. However, despite this success, sales started dropping (attributed to a recession in the art market), and Kasmin closed the gallery in 1972.

The chapter on 1964 covers the Painting & Sculpture of a Decade: 54-64 exhibition at Tate and the New Generation: 1964 exhibition at Whitechapel. Ticker gives these two exhibitions great credit, stating:

Together they registered a shift in the perception of British art, nationally and internationally, encouraging other sponsors and public bodies – the Arts Council, the British Council, and Jennie Lee as the Government’s first Arts Minister – to extend and develop their support for contemporary art in the absence of a dedicated London museum on the model of MoMA in New York.

This observation bears repeating. MoMa, established in 1929, was notably instrumental in developing the contemporary art scene in New York, and Britain did not have anything of a similar scale until the opening of Tate Modern in 2000.

The Tate Painting & Sculpture of a Decade show included 366 works by 170 artists from across the UK, US and Europe, and it aimed to show the progression in art during the period from 1954-65. The Whitechapel exhibition featured 12 artists: Derek Boshier, Patrick Caulfield, Antony Donaldson, David Hockney, John Hoyland, Paul Huxley, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips, Patrick Procktor, Bridget Riley, Michael Vaughan and Brett Whiteley. It was a young group, most under 30 and educated at the Royal College, the Royal Academy or the Slade. The show was curated to document the effect these 12 artists were having on the present and future of British painting. It is interesting to compare and contrast these two exhibitions; they were similar in terms of content and themes but very different in terms of scope and budget.

The detailed content in the ‘Installation’ section of this chapter is fascinating. It includes floor plans and images from the Tate show and reveals the extreme challenges the technicians faced installing the show. The exhibition architects essentially created tunnels, made of white screens, inside the museum rooms in order to play down the building’s architecture and compliment the contemporary art. It is hard to imagine this compressed format being a success. The reviews were certainly mixed, although the show did attract 95,000 visitors.

The installation itself is a sort of jolly, disinfected labyrinth more like an industrial design pavilion at an international fair than an environment for painting and sculpture, for which it is far too claustrophobic.

Roger Coleman in Art International

In summary, for me, this book’s value is as an academic or professional resource, but less as a book to read for pleasure or have on the coffee table to leaf through. It’s an exhaustive, well-researched compendium, just not a page-turner.