For ceramicists, every stage of their process is defined by risk. From the moment they centre the clay on the wheel, or they entrust a red-hot oven with their precious creations, they must accept the very real possibility of their work being ruined. With this risk, of course, comes disappointment and frustration but also, I’ve learned, there are happy accidents, uniqueness and the exhilaration of witnessing alchemy at work.

Every artist knows how to fail. Arguably, being an artist is an education in mistake-making. Each misstep will either lead you down a new, more exciting path, or it will inform and embolden your next attempt. Although this is a common experience amongst many creatives, none are better acquainted with the inevitable artistic gamble than those who work with clay.

I caught up with several local ceramicists – Ruth Baier-Rolls, June Gould, Julie Pearce, Andrew Sinclair, Clare Stotesbury and Lindsay Rutter – to find out more about how they navigate this chaotic medium and the day-to-day realities of being a ceramic artist in Jersey.

Although each of these artist-makers specialise in very different types of ceramic art, spanning homeware lines to one-off contemporary art objects, the first thing I noticed is how each of them credited those who first got them into ceramics. In fact, amongst them are two pairs of mentor-mentees: Andrew taught Clare at his home pottery and June first taught Ruth how to throw four years ago.

Like many other ceramicists practicing in Jersey today, Lindsay and Clare were also taught by the local pottery maestro Ray Ubstell and Julie spoke highly of David Brown who has supported and advised her throughout her career.

This may be unsurprising given how small Jersey is, but for me it spoke volumes about the way this craft is handed down from artisan to artisan. And through this community of shared expertise and resources, the medium shifts and changes in an alchemic blending of ancient techniques and modern-day experimentation.

As this process unfolds, ceramicists continue to draw on different sources for inspiration. One major influence shared by both Julie and Clare is the natural world. Julie tells me, adding:

Whatever I make, in my heart I’m making it for me, so my work reflects my tastes and interests. My swimmer and seabird ranges came about through my love of the sea and being near, in or on it. I’ve been a year-round swimmer and member of the Jersey Long Distance [Swimming Club] for several years. My bee range reflects my love of gardening and nature. I’m currently pondering using images of hens in my work next, inspired by the antics of the three feathered ladies that mooch around our garden!

In a similar way, Clare tries to recreate textures from nature in her ceramics. She explains:

While the kids are pointing out little Brazilian tree frogs at Jersey Zoo, I am there looking at the details in their skin, the colours, the shine, and the patterns; imagining how I can magnify these and use them as the motifs on pots, and choosing which colour glazes I would use.

For the others, shape and form, or in Lindsay’s case the way that the surface of the ceramics acts as a canvas, also captivate and motivate their practice.

With an art form that demands such specialised equipment, I wanted to find out how emerging ceramicists go about setting up their own practice locally. It was clear from the experiences of these artists that there are some incredibly skilled and generous ceramicists locally who share their expertise and equipment so others can pick up the craft – but beyond that, is there other support available in Jersey to help ceramic practitioners?

With no formal shared kiln/studio space or funding options for this type of equipment in the island, those wanting to start out on their own must either rely on the generosity of more experienced potters or to self-fund.

For Lindsay, who decided to leave the finance industry behind in favour of becoming a mature student studying ‘Ceramics, Metalwork & Printing and Textiles’ in Liverpool, the financial burden of setting up her own practice in Jersey may prompt her to look to the UK, where she says there are more opportunities available.

It is not easy to set up your own practice in Jersey, it costs a lot of money. There aren’t shared studio spaces where you can go. There are a lot of private individuals who have their own kilns […] But there is no funding available, specifically for setting up your own practice, there’s minimal support.

Coming to the UK, I’ve found there’s a lot more opportunities available […] there are shared kiln studios where you can pay a monthly subscription to a studio and use it up to a certain amount of hours and use the kiln, use their shared glazes. It would be amazing if there was something like that in Jersey.

Ruth echoed Lindsay’s call for a shared pottery workshop in the island:

Sadly there is no shared equipment available in Jersey, no kind of ‘open pottery’ like for example at the Art House Sheffield, where one can sign up, become a member and work with or without tuition. This means that one has to invest a considerable amount of money to get set up.

For Andrew, he described himself as “lucky” to have a pottery setup at home, but he told me that he sourced his kilns second-hand and only one of his three throwing wheels is brand new.

I use one home-made wheel [and] one ancient cone-driven electric wheel that I’ve had since I was eight years old!

June, who trained as a ceramicist in the 1980’s, also acknowledged that the cost of pottery equipment and space is often an obstacle for beginners. This issue is compounded by the high level of rent locally and the fact that “sadly, ceramic art rarely gets the price that a painting might command.”

Despite these challenges, each of the ceramicists I spoke to have all found ways to make work.

Lindsay, for example, has set up a subscription ‘Patreon’ page where admirers of her artwork can donate a small amount of money a month which she uses to buy more equipment and materials.

Mesmerised by all these potters’ ability to create such delicate forms out of a material as unruly as clay, I asked them how they grapple with balancing their own creative expression and the technical precision of the art form. It soon emerged that some were more vexed by this conundrum than others.

Ruth, a painting restorer by trade who is in the earlier stages of her ceramics career, thinks that the technical side of making pottery can be intimidating when you’re starting out.

I think that precision can sometimes get a bit in the way of the creative process, especially when one starts off as a ceramicist. One has to learn to let go and adopt a free approach, because that is exactly where the beauty of original work lies.

Whereas Andrew, who got into ceramics when he was still at school, rather argues that whilst finding a balance is tricky, the technical and creative aspects of the art form can also work in harmony. He explained:

Technically, pottery does throw up all sorts of challenges, although I have found that my technical knowledge helps when creating a sculptural piece. For instance, the support needed when attaching a tall, strap-like teapot handle helps my understanding of the properties, and therefore the limitations of the clay when creating an expressive piece of art.

Julie admitted that she finds the technical side of her practice “a chore and quite stressful”, but that is counterbalanced by the satisfaction of getting a piece “just right”.

As long as I can balance the technical challenges with the freedom and relaxation of an hour or two at the wheel, then I’m happy. And there’s always something new to learn and improve upon.

Indeed, both Lindsay and Clare are less preoccupied with achieving something that is technically ‘perfect’ and tend to focus on the process above all else.

Clare, who took pottery lessons as a child and then returned to the craft after watching the BBC Series ‘The Great Pottery Throwdown’, said the process is more important to her than the finished article.

For me, the most exciting part is being experimental with glazes, rather than focusing on precision and the finished product. This means I do have to embrace a lot of failure, as I never know how something is going to turn out. But for me this really adds to the beauty and excitement of pottery.

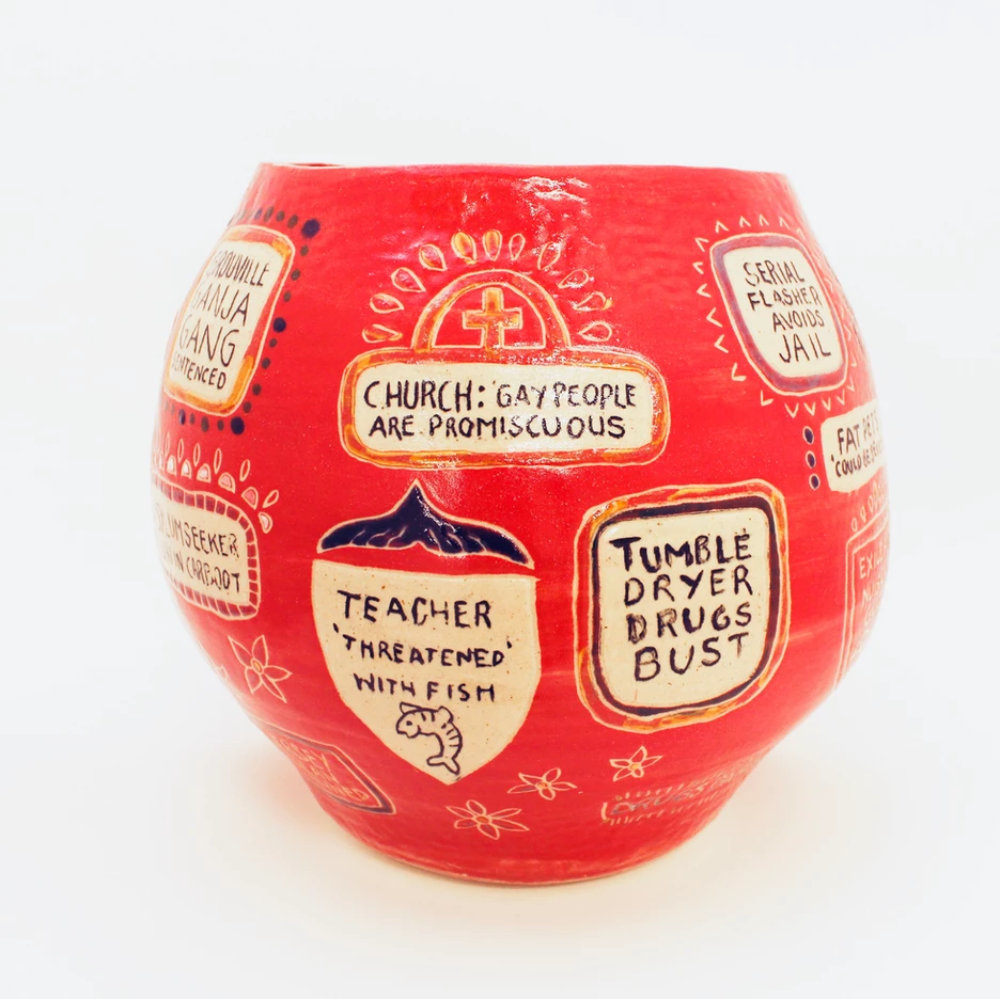

Art student Lindsay, who makes one-off large vessels which bear confessional texts carved into the surface of the clay, felt similarly, commenting:

I don’t intend to make multiples of one particular item, I like that each one is handmade and each one won’t be copied – you can’t replicate it because they’re all a bit wonky and they’ve all got their differences in them and little mistakes that make them unique. I love that.

Despite their differing experiences on how the precision of pottery figures in their work, all of the artists spoke passionately about how the unpredictability of the medium excites and stretches them creatively.

Experimenting with one of the most volatile firing techniques ‘Raku’ – a method which dates back as far as the 16th century and involves applying combustible materials to the surface of red-hot pottery – June has fully embraced the erratic aspect of ceramics.

Saying that she glazes “in quite a painterly way”, June celebrates the side of pottery which cannot be controlled:

My work is mostly stoneware fired in oxidation, but the pyromaniac side of me enjoys the adventure that is Raku. Based on Zen philosophy, Raku is a fast-firing method, usually en plein air. I am always exploring glaze technology, making all my own glazes. This is very much the art side for me – a pot is the vehicle I make to express and enjoy [myself].

This alchemy is quite magical, as all the various oxides and minerals from the Earth, can react together to produce fascinating reactions and colours.

Ruth too enjoys surrendering her creations to this extreme technique and revels in the organic quality of the medium as being “so deeply connected to the earth”.

Summing up the emotional extremes of the art form, Andrew remarked:

After all of this, the anticipation, thrill and excitement attached to the opening of the kiln after twelve hours of firing and two days of cooling, hopefully leaves the potter [with] a feeling of elation. Yet there are disappointments along the way and much to learn from each.