Ron Ellis

Street Art or Street Smart?

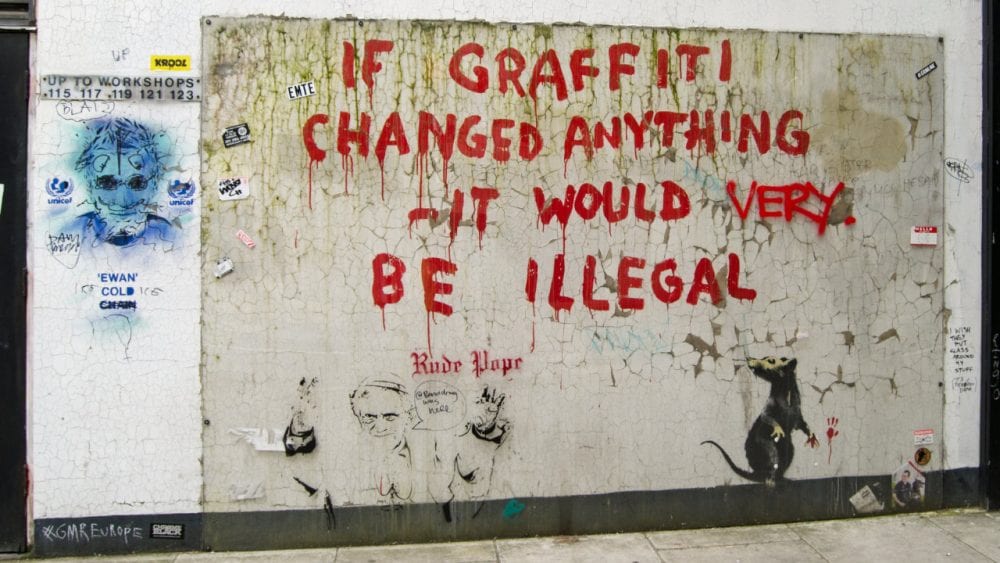

If you take a stroll through London’s Shoreditch or Nelson Street in Bristol, it’s hard not to admire the kaleidoscope of ‘graffiti’ adorning the buildings. This isn’t just flagrant youthful vandalism. This is art. In fact, it’s the art that has defined its own movement. This is Street Art.

Popularised in 1960s New York, the word graffiti on city surfaces, subway cars and trains established itself as a text-based urban communication, a dynamic art form of sorts – yet steeped in controversy. In the decades following this era, the graffiti movement spread across the globe. In the late 1970s and 1980s, graffiti writers started to shift away from purely text-based works to include imagery.

Unlike traditional artistic movements that span art history, street art is unruly and recalcitrant. It has a unique relationship with the society in which it is embedded – it is more of a creative diatribe than a conversation. There is no bilateral exchange between artists and their audience in the form of critique, galleries, auctions. There is no monetary attachment to the work or submission to the valuation criteria upheld by institutionalised art.

An inherent aspect of street art is its ephemerality. Any unsanctioned public work is created with a sense of awareness around its own transience, running the risk of being removed or painted over by authorities or other artists. The art cannot be owned or purchased, and it is this impermanence that creates an immediacy and a sense of subtle power around the work.

Early graffiti writers, followed by street artists, have developed an entirely new and separate art world free from dictatorial judgement about where it could appear and what it’s worth. Rather, it is based on their own conception of style, laced with a deeply embedded political voice about freedom, identity, and justice.

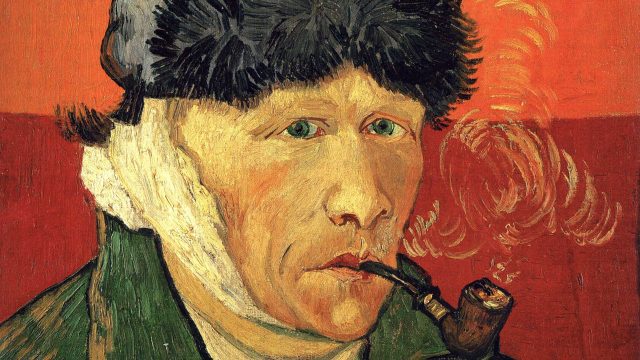

Banksy

He needs no real introduction. As a pioneer of the street art movement, the Bristol-based street artist has become one of the most globally recognised artists of our time, despite remaining relatively anonymous.

A lot of people never use their initiative because no-one told them to.

Banksy

Banksy

He uses the medium of art to create resonant social, political and humanist messages for the masses on a populous and public level. He has transgressed the shackles of the institution, defied cultural norms, and paved his own way to catapult guerrilla work into the mainstream as a viable form of art.

Photo by 1000 Words

To some people breaking into property and painting it might seem a little inconsiderate, but in reality, the 30 square centimetres of your brain are trespassed upon every day by teams of marketing experts. Graffiti is a perfectly proportionate response to being sold unattainable goals by a society obsessed with status and infamy. Graffiti is the sight of an unregulated free market getting the kind of art it deserves.

Banksy

And where Banksy has led, others have followed.

Dan Witz

New York-based street artist Dan Witz is renowned for subtle social messages through the medium of street art and has been an active player on the scene since the 1970s.

Back then, the idea was that if the world was a f****d up place that desperately needed changing, and contemporary art (and art schooling) had miserably failed us in this respect, then it became our job as artists to not only challenge the system but also change it.”

His main objective is to create works that almost blend into the street scene, subtle works that could easily be missed – but when they aren’t, they provoke a reaction. He famously chooses subject matter that makes a statement about his stance on the art world and contemporary issues.

Mixed Media on Condo Wall.

© Dan Witz

Street art has never been a means to get ahead for me. I still believe in anonymous, not-for-sale art as a meaningful response to art-world art – a genuine game-changer. And I still enjoy doing it, everything about it, especially penetrating into places that conventional art-making can’t.

Alongside his work in New York, he has also made a footprint on London streets, with heavy use of prisoners as a subject matter, often using doorways and windows – and even traditional red phone boxes – as a theme to represent institutionalisation. He was also involved in the Empty the Cages campaign (run by PETA), which aimed to raise awareness of animal cruelty in the meat production business. He created a series of emotive works in and around Shoreditch that carried through his infamous humanistic themes into the animal world.

© Dan Witz

Nick Walker

A British street artist who was a formative member of the graffiti scene of 1980s Bristol, Nick Walker, has, in the past, been dubbed as “the new Banksy” – owing to his use of the freeform spray can stencil imagery, laced with a political message about freedom and liberation from traditional street art.

In 2006 Nick famously created an alter ego, ‘The Vandal’ – a black-suited and bowler-hatted character that embodies the humoristic expression and irony that he sets out to achieve in his work. The concept behind the character is that he travels from city to city, throwing his palette of paint across high rise buildings and landmarks – his version of “painting the town red”, and appears predominantly in London and Paris.

Political statements are also deeply embedded in his work. He was known for his illegal piece – the famous Coran Can in Paris in 2010, which featured veiled women lifting their skirts to reveal stockings whilst they danced the cancan. The piece was intended as a commentary on President Sarkozy’s plan to ban the burqa in France.

While he produces thought-provoking pieces, it is with a lighter-hearted tone that Banksy’s socio-political work – but nevertheless, the impact is clearly felt.

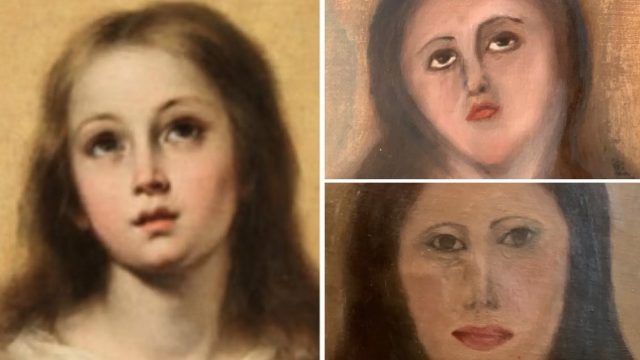

Chinagirl Tile

One of the much-revered female street artists, Chinagirl, is an Austrian-born self-proclaimed ‘activist artist’ who leverages her medium to send clear statements on social and political topics in cities right across the world.

© Chinagirl Tile

On the streets you can send out messages. On the streets it’s a visible space for everyone.

She has carved a niche with unusual ceramic works consisting of tiles, that she would then install in strategic locations by way of a social intervention; the pieces strongly connected to their environment. While she maintains that it’s not important for people to instantly understand her work, she wants them to “start thinking for themselves.”

With an emphasis on modern surveillance culture and the friction between the natural and the human world, Chinagirl’s unique format clearly follows in the footsteps of Banksy’s ‘activism’, but through adopting her own style she has created a name for herself in the global street art scene.

As an accessible artistic language that transcends both physical and online spaces, the primordial nature of street art is one of the most potent political tools throughout time. Shying away from convention, rules, laws, and institutions, street art has its own voice – and whether it is used hold up a mirror to society and the behaviour and systems that humanity project, or to reiterate a hard-hitting message – street art has proven its value in transcending history and borders. One thing is certain – the Banksy cult following is just one era of street smart artists that will earn a place in art history.