Wikimedia Commons

Artist Rivalry: Manet and Degas

Part 1/5

The contemporary art world has seen art schools proliferate, galleries multiply and artists increasingly able to market themselves and their works on their own websites and social media.

As technology makes it easier to put a variety and ever-increasing number of artists at the forefront of the public consciousness, we see each of these artists in a broader context. Unlike football, say, where there are a set number of teams that fans can follow, the field of ‘participants’ in art is unlimited; and the measures of success are less straightforward.

But this has not always been true. Before the rise of technology, the public became aware of artists through their admittance to Salons, inclusion in solo or group shows, or publicity through press or critic writeups. This meant fewer artists garnering attention, and artists often engaged in rivalries to be the ‘best artist of the day.

As time has passed, we often learn about these artists, their work and their legacy in isolation and not in relation to their contemporaries. We know about Matisse and Picasso, but we don’t know much about the relationship between Matisse and Picasso. Where known rivalries existed between artists, it is difficult to identify whether these historical rivalries were a product of the artists themselves or were a result of public opinion and pressure put on them by the critics at the time. Regardless, it becomes clear that attempting to understand these complex relationships helps us to understand each artist and their development better.

Over a series of five articles, we will examine famous artistic rivalries, the reasons behind these conflicts and the implications for these artists’ work.

Manet and Degas

Manet and Degas stand out as two of the most famous French Impressionists, alongside Bazille, Caillebotte, Cassat, Cézanne, Guillaumin, Monet, Morisot, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley. Manet was born in Paris in 1832, and Degas was in Paris in 1834. Both came from privileged backgrounds, and both became painters after disappointing their families by not following their expected career paths.

Manet’s career started as the stronger of the two artists. He was able to paint quickly, and his somewhat theatrical and staged portraits using models were generally well-received. His first major work, The Spanish Singer, was a success at the Salon of 1861.

Edouard Manet

Source: The Met

On the other hand, Degas painted slowly and painstakingly and struggled to get the critical acceptance that Manet was already receiving. It didn’t hurt that Manet found social situations and relationships easy; he was a gregarious and charming dandy, popular with men and women alike. Degas was more introverted and struggled to be at ease in himself and with others.

In the 1860s, however, the tides began to turn for Manet as he became more experimental in using colour and technique and the inclusion of morally “questionable” subject matter, as in Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. His reputation evolved from being publicly lauded to publicly mocked, and around the same time, his friendship with Degas began to increase in importance.

Édouard Manet

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Degas’ technique was very different to Manet’s painting process. Manet had no qualms about creating scenes to paint (in fact, errors and inauthenticities in his paintings were often pointed out to him), whereas Degas was persistently and painstakingly honest. So while Manet pulled Degas (and others) towards modernity as he consistently pushed the boundaries with his salon submissions, Degas followed with his own twist – a sort of psychological honesty of representation. He did this largely through the expressions he captured on his sitters’ faces, something Manet wholeheartedly avoided. The contrast between Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and A Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers is striking: Degas’s portrait is much more personal with more depth of feeling. Manet created scenes that were almost certainly imaginary or staged; in contrast, Degas created accurate, personal representations.

Edgar Degas

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Manet continued to submit experimental works to the Salons, never ceasing to be met with criticism. Degas hedged his bets more, feeling no need to submit work simply for it to be torn apart. When he finally submitted a painting he was happy with (The Bellini Family) in 1867, it was accepted but largely ignored.

Edward Degas

Source: Wikimedia Commons

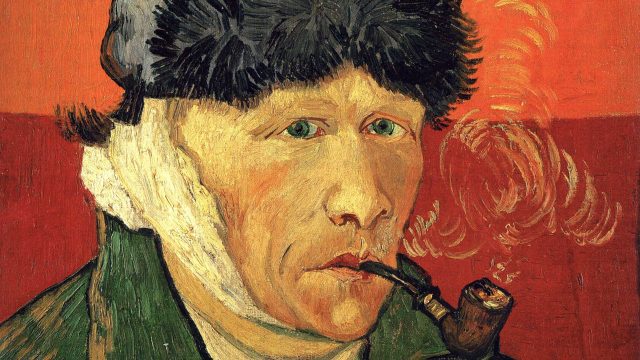

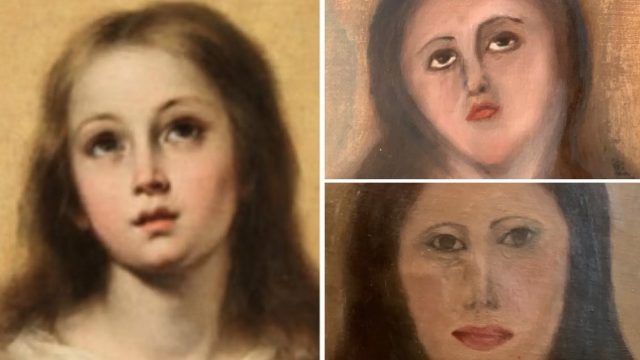

In 1868, Degas began to paint a double portrait of Manet and his wife, Suzanne. Manet reputedly fathered an illegitimate son with Suzanne before ultimately marrying her many years later. While they did remain married, Manet was a known womaniser. When Manet and Degas were both in love (or at least infatuated with) Berthe Morisot, Degas could not woo her, even though he was single, and Manet was not. Berthe went on to marry Manet’s brother as a sort of unsatisfactory consolation prize. When observing Interior, The Bellini Family and M. And Mme Edouard Manet together, there are compelling indications of Degas’ famously critical stance on marriage.

Manet and Degas fell out after Manet had a violent reaction to Degas’ finished portrait of the couple: Manet slashed the canvas where Suzanne’s face was painted. The piece remains on display today with her face cut away. The factors above likely played some part in the painting’s destruction, but we can never know for sure what Manet found so offensive. We do know that Manet went on to paint a portrait of Suzanne and Léon (her son and probably his as well) after the episode with Degas’ portrait, which suggests some element of compensation on Manet’s side.

Edgar Degas

Source: Wikimedia Commons

While the ruination of the painting was an extreme act, it surprisingly did not end the relationship between the two artists. Through the 1870s, Degas moved into his signature portraiture of ballet dancers and bathers, and Manet moved outdoors. They remained friends, in and out of each other’s studios. As Manet became ill in later years, he was forced to paint indoors but mimic outdoor backdrops. Degas remained a bachelor and became more and more reclusive in later years. His works continued to evolve in technique, colour and subject matter right up until his death.

Édouard Manet

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Manet died in 1883, and Degas died in 1917. Perhaps most tellingly, Manet had none of Degas’ works in his private collection at his death, but Degas had acquired eight paintings, 14 drawings and over 60 prints of his rival friend’s work.

Source and suggested further reading: Sebastian Smee’s The Art of Rivalry.