Wikipedia Commons

Artist Rivalry: Matisse and Picasso

Part 3/5

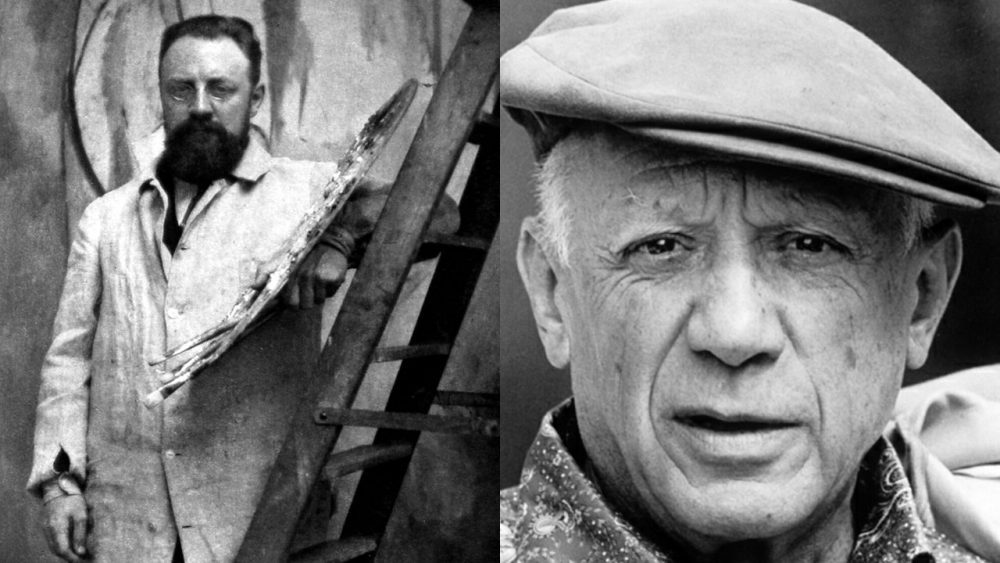

Henri Matisse was born on 31 December 1869 in France, and Pablo Picasso was born on 25th October 1881 in Spain. By the early 1900s, both artists had made their way to Paris and entered each other’s orbits. Their careers were to skyrocket, and their individual and collective legacy remains strong today. Only a few artists have changed the course of the art history as much as Picasso and Matisse.

In the early 1900s, Leo, Gertrude, Sarah and Michael Stein, a family of art collectors in Paris, were eagerly forging relationships with artists and collecting works. They allowed people to come to their homes to view their collections, and they hosted dinners and parties for friends and artists. Leo and Gertrude were avid early collectors and supporters of Matisse, and Matisse was a regular figure at these gatherings. Soon Picasso, and his then-girlfriend, Fernande Oliver, became regulars as well.

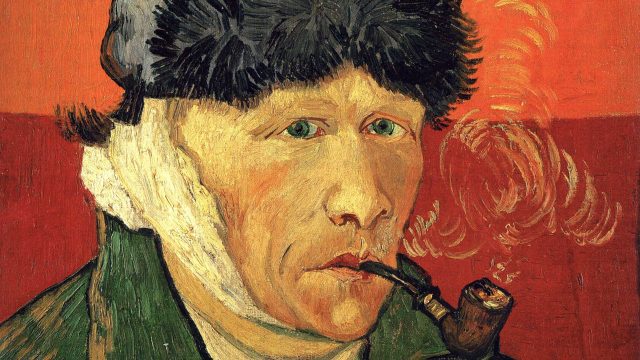

Henri Matisse

Collection SFMOMA San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Sarah and Michael Stein Memorial Collection, gift of Elise S. Haas

Copyright © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Source: sfmoma.org

In many ways, the artists were similar: both were consistently pushing artistic boundaries in ways that secured the signature styles they are still known for today. In other respects, they were very different. Matisse was slightly older, spoke French and already had an established network in Paris. However, he also had a family and financial obligations, which prevented him from leading Picasso’s more artistic, bohemian lifestyle.

Picasso had his studios in the Bateau-Lavoir, an established studio complex in Montmartre, where creatives of all types lived and worked. At various points, it was home to Guillaume Apollinair, Georges Braque, Kees van Dongen, Otto Freundlich, Juan Gris, Amedeo Modigliani and others. It was in these studios that Picasso began painting Gertrude Stein, encroaching on Mattise’s established relationship with this powerful family.

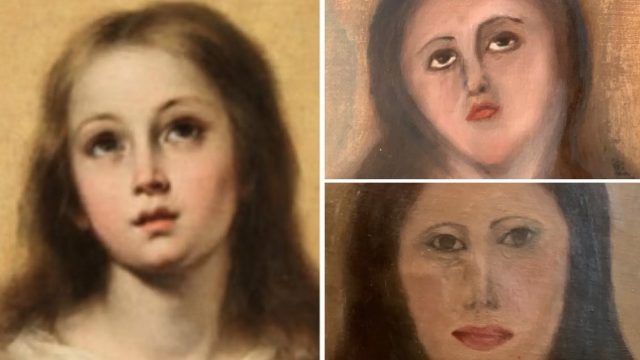

Source Wikimedia Commons

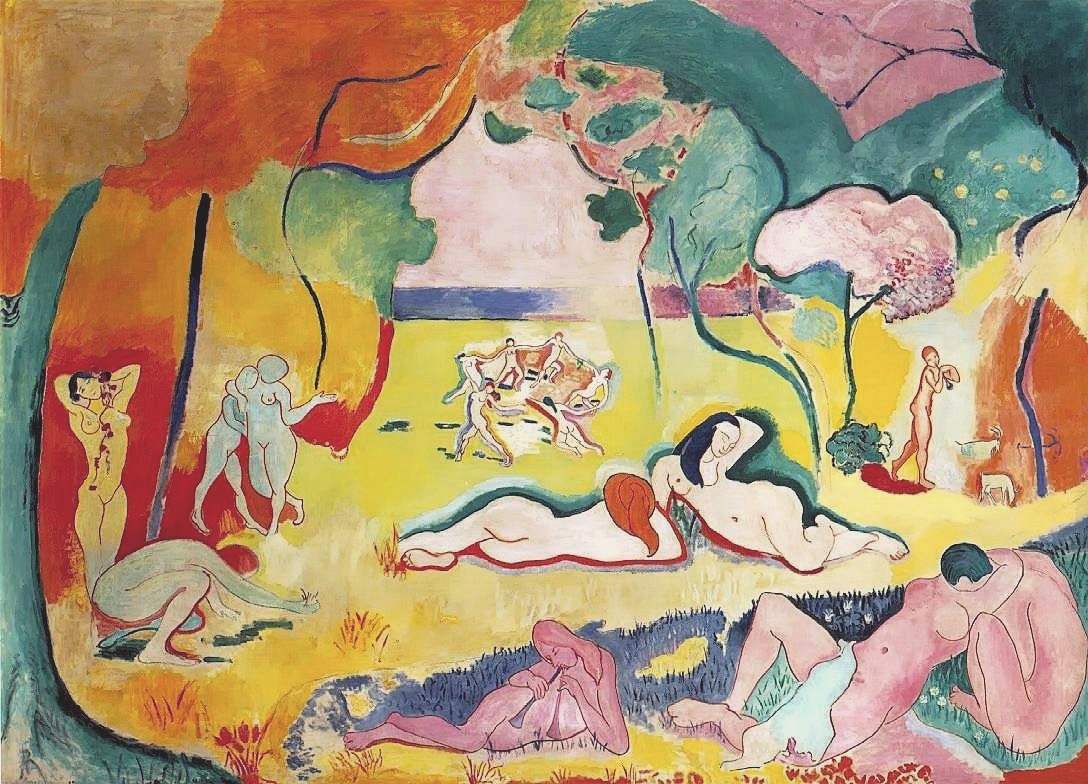

In 1905, Matisse’s innovation reached new heights with the submissions of Woman in a Hat and Le Bonheur de Vivre to the Salon des Indepéndants (a less restrictive alternative to the traditional and old-fashioned salons). At this point, Matisse and Picasso were continuing their artistic exploration, but they were developing in different ways. While Matisse was moving forward with (and ultimately beyond) Fauvism, Picasso was still painting relatively conservative representational pieces. The figures were recognisable; the colours were not unusually bright, and there was fairly little experimentation with perspective. It was Matisse who began exploring “deformation” (essentially distortion, whether by colour, outline or proportion). Picasso eventually developed his technique along the same lines, focusing on a sculptural quality drawn from ancient Iberian sculpture.

You have got to be able to picture, side by side, everything Matisse and I were doing at that time. No one has ever looked at Matisse’s painting more carefully than I; and no one has looked at mine more carefully than he.

Pablo Picasso

Henri Matisse

Source: Wikipedia Comons

Matisse’s work was gathering much attention and causing much confusion while on display at the Steins. Soon he was successfully working with Ambroise Vollard, one of the most prominent dealers in Paris. However, as the Steins were championing Matisse, they were also putting forward Picasso. With the publicity, the family fostered, Picasso was also added to Vollard’s repertoire.

Both Matisse and Picasso (along with many other artists of the time) were drawn to African art and carvings as a source of inspiration because of their abstraction of the human figure. Mattisse’s Blue Nude and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon both show this influence, which can also be seen in the German expressionist works of the era. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon received mixed responses critically, and it purportedly also called a rift between Matisse and Picasso; Matisse reportedly denigrated and dismissed his rival and suggested that Picasso was poaching ideas from himself and other artists.

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Pablo Picasso

From 1907, the support from Leo and Gertrude Stein, Matisse had become accustomed to receiving, began to wane. This endorsement was now bestowed on Picasso. Suddenly there was a divide between the followers of Matisse and the followers of Picasso. While Matisse remained commercially successful and had various shows, Picasso’s new style was catching the attention of other artists, who began to change their alliances. At this time, Braque invented Cubism – the movement that Picasso is now most well known for. Here, the rift between Matisse deepened; while Picasso and his followers experimented with Cubism, Matisse pressed on with his signature colourful paintings until finally, by 1913, he, too, began to dabble in Cubism.

These ebbs and flows in their relationship and styles reflect the extent to which they influenced each other, and by extension, the other artists in their periphery. Picasso and Mattise both had successful careers, and they remain two of the most famous artists ever. The depth and significance of their relationship are perhaps best summed up in one quote from Matisse:

Only one person has the right to criticize me. It’s Picasso.”

Matisse

The public appetite for their works remains strong: Matisse’s Cut-Outs were the subject of an exhibition at the Tate Modern in 2014; the Royal Academy held an exhibition about Matisse in the Studio in 2017, and the Pompidou had an online exhibition of Matisse’s works in 2020/2021. The National Portrait Gallery had an exhibition of Picasso’s portraits in 2016; Tate Modern had an exhibition about Picasso’s works during 1932 in 2018, and the Royal Academy held an exhibition about Picasso and Paper in 2020

The main source and suggested further reading: Sebastian Smee’s The Art of Rivalry.