This book review is the result of an accident. I ordered The Future of the Museum: 28 Dialogues by András Szántó (review to come), but when I arrived at the bookshop to collect it, The Art Museum in Modern Times by Charles Saumarez Smith was waiting for me instead. I confess to not realising the mixup until I arrived home and sat down with the wrong book, but by then, I was already engrossed. What a happy accident it turned out to be.

I can’t tell you the last time I sat down with a book on architecture and read it cover to cover in a day (and I studied Architectural Conservation, so I imagine that I’m significantly more likely to do so). This survey of museums from 1939 onwards was unexpectedly compelling and thought-provoking. In the course of reading it, I marked no less than 61 passages of note.

I am drawn to his writing style as one of my particular bugbears about literature on art or architecture is when the author’s tone, terminology and language which almost necessitate the reader’s previous knowledge of the subject to make heads or tails of the content. Writing on these topics does not need to be elitist and prohibitive to comprehend.

I am now yearning to discuss the current state of art museums with anyone willing to listen. I would love the opportunity to sit down with the author, Charles Saumarez Smith, to hear his criteria for selecting the museums for the book and inquire about other institutions I would have expected to be included, for example, Frank Gehry’s Fondation Louis Vuitton or Glenstone but I suppose a comprehensive survey would not have been viable in this format.

Charles Saumarez Smith was the Secretary and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy of Arts in London (2007-2018), the Director of the National Portrait Gallery (1994 to 2002) and the Director of the National Gallery (2002 to 2007). He began writing this book in 2018 when he was still at the Royal Academy. The book went to print in 2021, allowing him time to comment on the effect of the COVID19 pandemic on museums and the arts.

David Chipperfield’s Royal Academy of Arts

Source

Important to note: for those who would like to read this as an architectural survey of significant modern art museums built, adapted, restored or expanded in this period, read this book and omit Chapter 5 (key issues). The chapter addresses more political rather than design aspects. Even without this chapter, this would have been an exceedingly absorbing read (although perhaps light on accompanying images). Still, this assessment of key issues is really what distinguishes the book from architectural history and moves it firmly into a commentary.

While Charles Saumarez Smith concludes the book with the following 5 ways museums today are under attack, I am going to share them first:

- Fear of criticism of the wealth of founders, donors, board members, and sponsors (the public is increasingly critical of excessive wealth and wealth gained in ways they feel is immoral)

- Issues surrounding restitution: Should museums be allowed to keep works they purchased but may have been looted originally? Should museums only show works from their own cultures or countries?

- Assault on the canon: There is no longer a belief in a master narrative of the art history and an understanding that we see art history through their bias, who has been able to make art, what art has been recorded.

- Failure to address the legacy of slavery in a systematic way. While it is not unique to the arts museum sector, it is still an issue.

- Effect of the COVID19 pandemic on funding: Arts budgets have been cut and may not be reinstated. Will museums continue to fund offline exhibitions, or will there be more online exhibitions as we advance?

He portrays these challenges against the evolution of audience expectations of museums: from being “sources of academic authority” to serving as venues where individuals can inform themselves and make their own judgments or absorb, relax and explore at will. He also identifies the fundamental difference between public and private collections. While public collections essentially must use taxpayers money for identifiable public benefit, private museums can create spaces of contemplation outside the everyday world, free from the demands of consumerism, treating works of art as objects of more purely aesthetic experience. Charles Saumarez Smith also discusses the role of the architect, the function of the client, the changing characteristics of art, globalisation, and the rise of the digital world – all within the context of the implications for museum spaces.

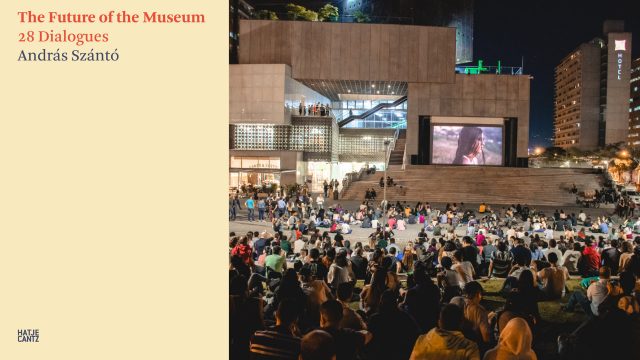

Guggenheim Bilbao

Source

The book’s main body addresses 4 movements in recent museum history as identified by Charles Saumarez Smith: The Modern Museum, the Postmodern Museum, Museums for the New Millenium, and the Museum Reinvented.

The Modern Museum phase includes examples from 1939-1978, characterised by systematically displaying works to explain the narrative of the history of art. Postmodernism (examples from 1984-1997) led to challenging the idea of temporal, geographical or cultural narratives and seriousness around the history of art. It also saw the rise of statement architecture, like the Guggenheim Bilbao, which led to the Bilbao effect (a belief that a showstopper architectural commission will reinvigorate an area). In the new millennium (examples spanning 2000-2011), museum architecture was expected to be more sympathetic to the environment and collections and less an opportunity for architects to build showy, somewhat gratuitous statement pieces. Within museums themselves, there was a move to egalitarianism between spaces (exhibition spaces, administrative spaces, shops, and cafes). The Museum Reinvented phase (2011-present) is an era where museums are seen as gathering spaces for people to explore at will, on their own terms.

Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

Source

Charles Saumarez Smith gives examples of museums and discusses their conceptions and their receptions. Those you would expect to be included are MoMA New York, Guggenheim New York and Bilbao, Centre Pompidou, The Louvre Pyramid, Getty Centre, Tate Modern, Whitney, Broad, and Royal Academy). However, the real joy is reading about the lesser-known examples such as the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, the Kimbell Art Museum, The Barnes Foundation, The Menil Collection, Benesse House Museum, Kolumba, MONA and Muzeum Susch. My favourite inclusions were the São Paulo Museum of Art, Louisiana, Dia:Beacon and Beyeler Foundation.

The São Paulo Museum, designed by Lina Bo Bardi, has art pieces hung on suspended pieces of transparent glass anchored in concrete blocks. Louisiana was specifically located outside of the city. Close to the sea, it feels very anchored in nature, allowing visitors to be relaxed and absorbed in the surroundings, not just the art.

Dia:Beacon was a project undertaken by the Dia Foundation, which also funded Donald Judd’s projects in Marfa (now the Judd Foundation and the Chinati Foundation). Like Louisiana, they wanted to move the Dia Centre for the Arts collection out of the city and into the Hudson Valley. They found a semi-derelict Nabisco factory, where they did a relatively minimal intervention. They allowed Robert Irwin (light artist) to design the layout, giving the artist fundamental control over how artworks should be seen. The Beyeler Foundation, designed by Renzo Piano, was designed along the same lines as the Menil Collection in Houston and encouraged guests to use the space as a place of reflection, similar to museums in Japan. Piano felt strongly that the architecture should not overshadow the artworks, saying:

There’s no such thing as neutral space. Neutral architecture is pointless architecture, like soup that tastes like nothing, or a boring novel. But it’s equally clear that a museum should let the work of art take centre stage. It’s wrong to think that the quieter you are, and the less present, the better it is for the exhibit, but of course you can kill off art with all this neutrality. On the other hand, you don’t really create the right space for an exhibit with shapes and extravagances. You need light, proportion, and materials.

São Paulo Museum of Art

Finally, I must admit that my background in art/architecture no doubt influenced my appreciation of this book. In my experience, visiting museums has been a two-fold experience. As much as I was visiting to take in the art, I spent considerable time looking at the building itself, thinking about how it shaped the way I was absorbing the art and being drawn to particular paintings.

From a professional view, as a Loans Registrar at an international art gallery, I couriered (accompanied) paintings to museums (including many featured in this book). On these journeys, I constantly faced challenges installing, moving, and showing art in architect-led premises. Almost universally, the spaces were not designed for easy transit of crates (required for most high-value artworks); walls were not plentiful enough, flat enough, or wide enough; temperature and humidity controls were inadequate; light levels threatened to degrade artworks, and on-site storage was an unattainable utopian dream. (One of my lunchtime routines on rainy workdays was to wander over to the Tate Modern and look for the surreptitiously placed buckets to capture leaks in the new Switch House.)

Tate Modern Switch House

Looking beyond structural challenges, I believe that we place a high value on the role of a curator in a museum show: how the paintings are hung, in what order, what is included, how much context or explanatory text is provided and so on.

But what if museum shows treated the space itself as a curator? What if shows only travelled to venues that would best suit the works? Do you take away more from viewing an artwork or an artist based on its environment? Is it better for you to notice the environment or not to notice it at all? Is it right for a museum to juxtapose an artwork: should it complement it or should it remain invisible? What do I expect from a museum now, and has that changed since I started visiting museums as a child?

These questions I take away to consider further, spurred on by the points that Charles Saumarez Smith raises in this text.

*All quotes come from The Art Museum in Modern Times by Charles Saumarez Smith