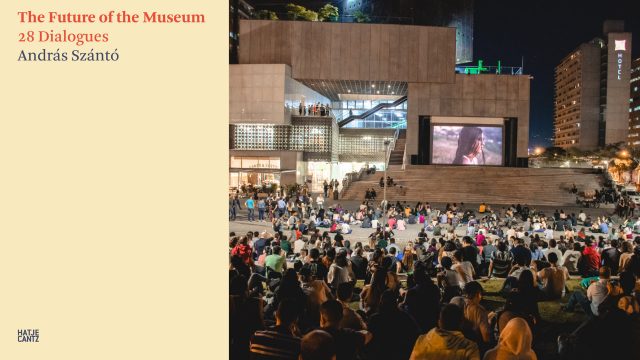

Book Review: Letters to Camondo

Edmund de Waal is most well known for his assemblages of porcelain vessels, often arranged within purpose-made, wall-mounted display units. His ceramics are muted in colour, with soft curves and occasional gold accents. The arrangement and display are as intrinsic to understanding the piece as is the form itself.

In 2010, de Waal published The Hare With Amber Eyes, to great acclaim. It tells the story of his Jewish ancestors in Paris, the Ephrussis, and the fate of their great art collection before, during and after World War II. Letters to Camondo is in some ways a follow up to The Hare With Amber Eyes but also stands alone as a touching and unusual memoir to another Parisian Jewish family, the Camondos.

Edmund de Waal

Source: edmunddewaal.com

The Musée Nissim de Camondo sits at 63, rue de Monceau, just a few doors down from the Ephrussi family home. Today, visitors to the museum step through the doors and see the home precisely as it was the day Moïse Camondo died in 1935. Everything has been left as he wished; Moïse even specified how space should be cleaned. De Waal likens it to the Wallace Collection, London and Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, in terms of the dedication to preserving the past exactly. De Waal likens the Camondo house to a Cornell vitrine – and although equating an ‘assemblage’ to Cornell is perhaps a bit cliched, it is one cliche most would be happy to accept.

Letters to Camondo is the history of the Camondos in the form of contemporary letters de Waal writes to the long-deceased Moïse; or as de Waal explains at the outset, ‘Dear Friend, I am making an archive of your archive.’ De Waal writes to Moïse about aspects of their family history, his life and the fate of their families and art collections in compelling essay-like form. Each letter covers a different topic, largely non-chronologically, but the result is a clear, touching, and often tragic portrait of a family closely linked to de Waal’s own. Unless you have an uncanny knack for remembering names, you will find yourself leafing back through chapters, trying to understand how the families are related or have intermarried; after much subsequent internet research to try to make sense of it, I can say that a family tree would have been a welcome addition.

De Waal writes many of the letters while sitting inside the Camondo house, asking Moïse about his collection and the process of designing the house and collecting its world-renowned furniture, artwork and ceramic contents. Like many of the prominent Jewish families in Paris before World War II, Moïse’s family was from elsewhere (Constantinople, now Istanbul), but settled in Paris. The area around the rue de Monceau became populated with Jewish families like de Waal’s (the Ephrussis), the Rothschilds, the Hirschs, the Bambergers, the Sterns and the Reinachs. They came and built grand houses, many of which still stand today, and began to assimilate into French culture (another point that de Waal is keen to reinforce). De Waal romanticises this period, saying ‘this is a Londoner writing to you. We live opposite a school and our street is full of huge cars and slammed doors at this time of day, dammit.’

An overarching theme throughout is de Waal’s cultural reckoning, a result of family migration and having been brought up in the United Kingdom. He introduces this theme early on, with quips like:

As I am mostly English I want to ask you about the weather…this is how the English ask how you are. We talk about the weather. And trees

It’s something he revisits both in terms of the Camondo family as well as his own. He notes how Moïse seemed keen to become French; Moïse auctioned off family and religious heirlooms from Constantinople and rebuilt his parent’s original house in Paris to be more tasteful and fashionable. De Waal notes how he, himself, has been queried about his potential ‘coming back’ in reference to faith, but his identity is multifaceted. De Waal reveals that he was raised in the Church of England; he feels compelled by Quakerism and Buddhism; and that being half-English, a quarter Dutch, a quarter Austrian and completely European muddies the waters of his identity.

The link between de Waal and Moïse becomes clear with the introduction of Louise Cahen d’Anvers, who was married to Comte Cahen d’Anvers but had a long-standing affair with Charles Ephrussi (de Waal’s great-grandfather’s cousin). Moïse marries Iréne, the oldest daughter of Louise and Comte Cahen d’Anvers, and they have two children, Nissim and Béatrice. The marriage to Irène is short-lived; de Waal hints at the 12-year age gap as a contributing factor. Moïse lives next to the Reinach brothers (Joseph, Salomon and Théodore), and Nissim attends the Lycée Condorcet with Fanny Ephrussi (neice of Charles Ephrussi) and Theodore Reinach’s son, Léon. Béatrice and Leon marry and have two children, Fanny and Bertrand. Unfortunately, tragedy strikes the family on a fairly all-consuming scale. Nissim dies after being shot down in World War I. As antisemitism rises during World War II, Béatrice and Léon divorce, and Béatrice converts to Catholicism (what appears to be an intention to protect the children). But her efforts are to no avail. Béatrice and Fanny are deported to a concentration camp first. Léon and Bertrand follow not long after. All four ultimately die, as do other members of the family. Art is confiscated. Family homes are ripped apart.

De Waal says he writes this book as a tribute to a lost family and their collection that lives on. He also notes “that people slip into art and are lost” in reference to the surviving portraits of family members and their own journeys. There is the portrait of Irène Cahen d’Anvers by Renoir, which was confiscated by the Nazis, selected for Goering’s collection, later chosen for Gustav Rochlitz’s collection, sent back to Paris, and finally reclaimed by Irène in 1946, who became the heir to the Camondos being the last to survive. She then sells it to Emil Georg Bührle, who was a supplier of armaments to the Nazis, and it remains in the Fondation Bührle in Zurich today.

Auguste Renoir

Sammlung E.G. Bührle

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It is rare to get insight into de Waal’s work in the book, with its focus clearly on the Camondos, but there is a moment where de Waal likens Moïse’s arranging to his own practice:

You put this here and set off small chords, echoes and repeats and caesuras. You put it there and it is just stuff, gilded and valuable but still stuff.

It is what I do in my studio. I make my porcelain vessel and I’m keeping a phrase from a poem or the shape of a fragment of music in my hands and head as I throw one after another, the balls of clay on my left, my ware boards waiting on my right. And a few hours later when they have lost some of their dampness, I trim them, searching for the balance between outer profile and inner volume. Then firing. And glazing and firing them again. And then I have my moveable porcelain vessels to congregate and space, remove and replace, trying to find those moments when, if you get it right, the cadences keep going.

The book includes recommendations for further resources, and of course, reading de Waals first book is recommended to give a broader picture. But the real gems are the inclusions of little stories like the following:

And then that makes me think of the bunch of asparagus that Charles bought the same year from Manet, off the easel. The price was eight hundred francs and Charles, open-hearted and open-handed, sent a thousand. And then four days later a small canvas with a solitary asparagus spear is delivered to the rue de Monceau, a scribbled M in the top right-hand corner with Manet’s note, “this one has slipped from the bundle”.

Édouard Manet

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Overall, Letters to Camondo is a quick read, easy to get engrossed in and leaving one with a desperate yearning to get on the Eurostar to Paris immediately.