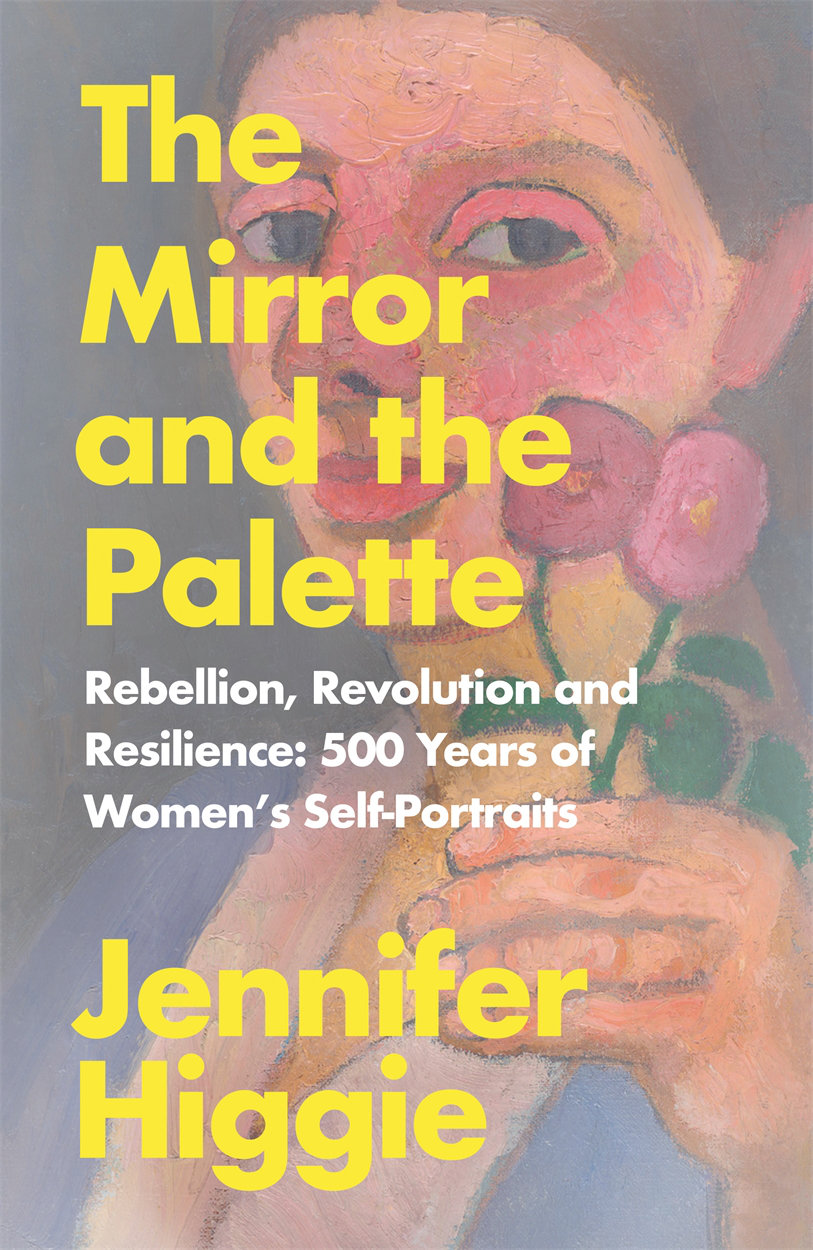

Prior to seeing this book on the shelves of my local bookshop, I was familiar with Jennifer Higgie as the editor of Frieze Magazine and a frequent panelist in arts discussion (a quick Google search of ‘in conversation Jennifer Higgie’ yields pages of results). I wasn’t aware that she was an author.

For someone that can often find non-fiction a slightly tedious journey, I found The Mirror and the Palette – Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience: 500 Years of Women’s Self-Portraits to be an unexpected page-turner. Higgie’s voice comes through in the commentary, making the reader feel more as if they are sitting opposite her in a coffee shop, rather than reading a 328-page compendium on women’s portraiture. She manages to be wry, funny, and opinionated; and she deftly handles topics and themes that have become ‘problematic’ in recent years.

The prologue presents a brief history of women artists, charts the barriers they have had to overcome to be able to paint over the centuries, chronicles how women have been accounted for in art history, and identifies the impact of feminism on womens’ abilities to be career artists.

My only criticism of this book is it’s organisation: Higgie frames the content into seven chapters addressing the themes of Easel, Smile, Allegory, Hallucination, Solitude, Translation and Naked. Aside from the pedant in me that would prefer ‘Naked’ be ‘Nudity’ for consistency, I found the themed chapters slightly distracting. I appreciate the desire to step away from a typical historical survey by century or decade, but with each new chapter, I felt hard pressed to identify the linear progression of women as self-portraits. What was clear was that the last 500 years have been an uphill journey for women artists. There are startling differences in the pace and milestones of each journey, influenced by where the artist was born, was raised and practiced – as exemplified by Loïs Mailou Jones’ varied experiences as a black female artist in the US versus France.

In ‘Easel’, Higgie begins with the first recorded self portrait completed by any artist: Catharina van Hemessen in 1548. Higgie shares what is known about the lives, careers, deaths and legacies of other early female artists such as Sofonisba Anguissola, Mary Beale and Marie Bashkirtseff. Higgie notes that early artists’ legacies were ensured if they were included in texts on artists written at the time (like Vasari’s’ The Lives), or if they kept detailed records themselves. Somewhat sadly, the female artists we do know about are generally those who could write – leaving one to wonder how many paintings were not signed and how many painters have been erased from history because nobody wrote about them and they couldn’t write about themselves.

Self-Portrait by Catharina van Hemessen, 1548

Self-portrait 1548

Source: Commons/Wikimedia

“Smile” addresses female artists who pushed the boundaries of acceptable moral representation in their self-portraits. She notes that smiling in paintings was seen as immoral – with a cutting note that ‘this might have had something to do with the fact that King Louis XIV had no teeth left by the time he was forty and it wasn’t done to gloat’. Sofonisba Anguissola, Judith Leyster and Elisabeth Vigeée Le Brun are given as examples of women who pushed the boundaries of what was morally acceptable in self-portraiture at the time. Higgie notes that often talented and successful female painters fell victim to men slandering them, accusing them of immorality, or casting doubt that they had the ability to create the paintings themselves.

“Allegory” delves into the allegorical elements of the self-portraits: how women used objects, symbols, postures and allegorical details in their paintings to communicate about themselves, their situation and their view of life. Higgie notes that beyond the artistic merits of this practice, artisans (those painting commissions for patrons) were often subject to greater taxation than artists. In some cases, there was a financial benefit to adding hidden or inferred meaning to a painting rather than creating a literal representation. Higgie covers Artemisia Gentileschi (who was raped by her teacher and was subjected to a brutal trial), Elizabetta Sirani (who not only painted but also opened the first school for women artists in Europe in Bologna in the 17th century), Rosalba Carriera (the first artist to paint on ivory and achieved phenomenal success in her lifetime), Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser (the two female founding members of the Royal Academy), and Laura Knight (the first woman to be admitted to the Royal Academy, 136 years after Kauffmann and Moser were made founders).

“Hallucination” moves significantly further forward in artistic movements, focusing mainly on Surrealism and the Dadaists. Higgie’s definition of the Dadaists is one of the best I’ve come across: ‘for the Dadaists, absurdity was a way of simultaneously expressing the uneasy relationship that exists between the deep mysteries of the self and the often bewildering and bureaucratic machinations of daily life.’ She provides ample evidence to suggest that while there were female artists who were acknowledged and accepted by the Surrealists, the women were taken less seriously than their male counterparts and were expected to first perform their ‘roles’ as mothers and wives. When Peggy Guggenheim staged her famous ‘31 Women’ exhibition, Georgia O’Keefe apparently didn’t want to participate and subscribe to the label of ‘woman artist’ – demonstrating that the debate on the moniker, ‘woman artist,’ is certainly not recent. Frida Kahlo was also not keen on labels of any kind, later saying, ‘I never knew I was a surrealist till André Breton came to Mexico and told me I was.’ While Higgie touches on Kahlo’s much-discussed volatile relationship with her husband, Diego Rivera, she observes something I hadn’t heard before: both Rivera and Kahlo’s final paintings were of watermelons, which Higgie asserts is a symbolic self-portrait on Kahlo’s part (and perhaps an ode to Kahlo on Riveras part?).

“Solitude” broadly discusses artists for whom solitude was both a way of life and of producing paintings. There is a disheartening congruence in the women’s stories: they all struggled to find lasting romantic connections, contended with mental health issues and died in solitary circumstances. Higgie includes a quite devastating portrayal of the life of Helen Schjerbeck – who as early as 1905, was rejecting the idea of shows comprised of ‘women artists.’ Higgie details the life of Gwen John, whose brother Augustus John was considerably more famous and successful, despite him declaring, ‘Gwen has the honours or should have – for alas, our smug critics don’t appear to have noticed the presence in the Gallery of two rare blossoms from the most delicate of trees…’. Nora Heysen struggled to have an enduring career in the shadow of her successful painter father, with a particular weekly publication running an article on her titled, Girl Painter Who Won Art Prize is Also a Good Cook.

Self Portrait by Gwen John, 1902

Self Portrait 1902

Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Source: tate.org

“Translation” deals with artists who had to experiment with and learn ways of painting that suited and represented a post-colonial experience. As previously mentioned, Loïs Mailou Jones lived and worked in a time in America where being black and female was perhaps the biggest handicap an artist could have. Jones was told that it was not enough for her to create art and exhibit in ground-breaking shows; her art also needed to contribute to the civil rights movement. To comply, she changed her style and subject matter, creating art that incorporated African motifs and icons. Rita Angus and Amrita Sher-Gil are other women who grappled with issues surrounding cultural representation in their self-portraiture. While Sher-Gil’s tragically short life and career granted her success, Angus died in 1970, little known outside of New Zealand. A retrospective of her work was planned for 2020 at the Royal Academy, but it was postponed due to COVID19.

Finally, “Naked” discusses women employing nudity in their own terms in their self-portraits (as opposed to nudity through male representation). Despite the rankling word choice, I found this chapter by far the most interesting. Higgie delves into the life of Paula Becker (Paula Modersohn-Becker), who painted the first naked self-portrait. Even more groundbreaking, she painted herself as pregnant. Becker was not actually pregnant but was using the depiction of pregnancy as an allegory for her creative output. The story of her life chronicles a series of episodes where she leaves and later returns to her husband because of the creative freedom she seeks, the burden of responsibility she endures, and the financial security she possesses when she is reunited with him. Some of her naked self-portraits were staggeringly progressive, but they were not shown in her lifetime. She only sold three works before her untimely death after childbirth, aged 31.

Self-portrait on the 6th wedding anniversary by Paula Modersohn-Becker, 1906

Self-portrait on the 6th wedding anniversary, 1906

Source: Commons/Wikimedia

Alice Neel finally achieved a measure of success and recognition at age 70. After painting countless portraits of others, she painted her first self-portrait at age 80, naked in her chair. Higgie highlights Neel’s refusal to follow artistic movements or trends, persisting with portraiture when others experimented with abstract expressionism. While she eventually (particularly in recent years) received much admiration and exposure, she was sidelined throughout much of her career. Higgie quotes Peter C. Marzio as saying, ‘What was the best way for an American artist to be ignored during the middle of the twentieth century? First, to be female. Second, to paint portraits. Third, to be an independent thinker with a sharp intellect. Alice filled the role like an actor straight out of central casting.’

Self-Portrait by Alice Neel, 1980

Self-Portrait, 1980

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Copyright © Estate of Alice Neel,1980

Overall, The Mirror and the Palette was an informative read, full of gripping and unexpected anecdotes. Even in the case of artists like Frida Kahlo, for whom it is unusual to read something ‘new’, Higgie manages to bring forth a narrative that feels fresh and remains interesting. She paints a clear picture of the factors influencing women’s self-portraiture over the last 500 years: struggling early in their careers, persisting post-marriage, and striving to receive recognition. As might be expected, Higgie is unable to go into great detail in the vignettes about each artist – to do so would require a publication of impossible size. However, she gives just enough detail to inspire you to go away and do more research yourself – which ultimately is exactly what a book on this topic should do.

*All quotes come from The Mirror and the Palette – Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience: 500 Years of Women’s Self-Portraits by Jennnifer Higgie