Image © Charlie Haydn Taylor

Women in Art: A Celebration of Artistic Femininity Through the Ages

In recognition of Women’s History Month in March, Connect With Art presents its first curated virtual exhibition exploring the theme of ‘femininity’ and ‘women’. As a prelude to this, we’re exploring the depth of artistic femininity through the ages.

I do not wish women to have power over men; but over themselves.

Mary Shelley

From idealised Roman warrior queens and mythical ancient Greek goddesses, through to fulsome women of the Renaissance era, art has shaped female beauty ideals across the course of history, rendering gender a deeply embedded theme in its representation of society through the ages.

History provides us with a record of the portrayal of women, and from it, one inescapable, and ultimately unconscionable truth stands out: the ideals women are asked to embody, regardless of culture or continent, have been repeatedly visualised almost exclusively by men. Owing to the prevailing values and as a result of long-standing cultural and social structure, the reality is that female artists have mostly been devalued in art history.

As a subject, women have played an integral role to the aestheticism of female ideals. From some of the earliest recorded pieces of art which celebrate femininity, the role women have played throughout art history has predominantly been one of passive objectification. When depicted artistically, passivity is the norm; whether manifested as softness, slack musculature, or a deferential pose – embodying sexuality or innocence. Whichever era one references, this theme remains consistent.

Aphrodite of Knidos, Praxiteles, c.350 BC.

One of the earliest recorded sculptures of the first female nude statue – which despite being destroyed later – lives its legacy through countless replications, was the Aphrodite of Knidos from 330 BC, made by Praxiteles. He destroyed conventional assumptions about art and gender, creating a goddess in human female form and sexualising it in a way that stretched beyond the social bounds of expectation.

This marked the start of an edgy relationship between an artistic statue or portrait of a woman and an assumed male viewer that has never been lost from the history of European art and has since manifested in endless ways and through countless different mediums.

Bikini Girls, 4th Century AD

The piece which subverts this trend forms part of a mosaic found in the early 4th-century Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily. The “Bikini Girls,” as the piece is known, provides one of the few celebrations of the female figure performing athletic acts, other than dance, in the history of art.

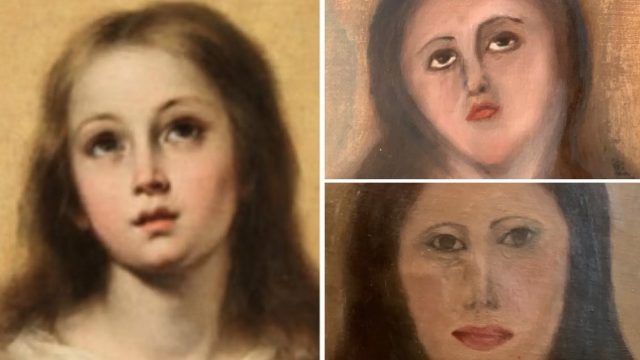

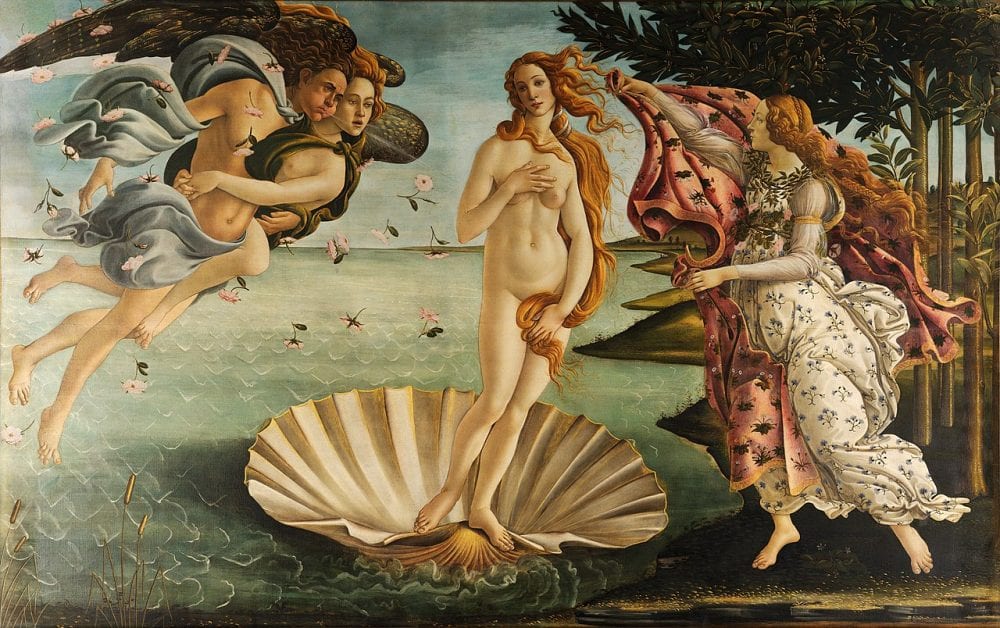

Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, 1485

Later on, the Renaissance era was characterised by men who viewed women as a tool to display wealth and lineage; nudity and sexuality were core themes explored by artists of this era, and the presence of female artists. The adversity faced by female artists of the Renaissance period included acquiring the necessary skills without completing an apprenticeship, and because apprenticeships were inappropriate for women, female artists were usually trained by their fathers. Furthermore, women were forbidden to draw from the nude model, so women often concentrated on the painting of portraiture, still-lives and devotional panels.

Created in 1485, the Birth of Venus is perhaps one of the most famous paintings of its time, depicting Goddess Venus arriving on the island of Cyprus, a symbol of purity and perfection.

Olympia, Edouard Manet, 1863

When it was first unveiled in Paris in 1865, Manet’s masterpiece was deemed “shocking”. Despite the nude female form being at the centre of art as an enduring and universal subject, the scandalous nature of ‘Olympia’ was owing to its depiction of a prostitute. A portrayal of the cold and prosaic reality of a truly contemporary subject, Venus, the female subject, is challenging the viewer with her calculating look, and this profanation of the idealised nude was a controversial move from the upper-middle-class art. Moreso, Manet portrays the maid, the model was later identified as Laure, as a fully clothed wage-earning woman, opposed to, traditional for the time, bare-breasted exoticized servants in harem settings.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907

The famous painting, which translates to “The Young Women of Avignon,” refers to Avignon Street in Barcelona, home to the prostitutes the artist frequented. Broadly regarded as immoral when it first exhibited in 1916, the five women’s nude bodies are depicted with angular lines and flat, geometric planes, their faces inspired by African masks. Known for his provocative artistic flair, Picasso painted the women with detached expressions staring straight into the eyes of the viewer, symbolising their role in society as objectified yet empowering them with self-possession.

For Every Fighter a Woman Worker, Adolph Treidler, 1918

This very socio-political artwork was a propaganda poster from World War I, and depicts a female munitions worker with the elegance, poise and beauty of a classical statue. In reality, the work she advertised was dirty, dangerous, physically demanding, and attended by frequent explosions and instances of chemical poisoning. While the poster emphasises the need to “Care for Her Through the YWCA,” ultimately, there was heavily subliminal messaging around her moral as well as physical welfare. The classical beauty of the figure helped to reassure women that their femininity would not be compromised by such work.

Women and their central role in art

Gender discrimination in art has been largely about the representation of women with sexual identities or roles attributed to them. From ancient works, through the medieval period and into new age, generally, two main prototypes of the theme were created: the seductive and fallen woman and the angel mother and spouse with naive, weak image iconographies.

Contemporary art has worked harder to subvert the ideology of the female form and has moved away from the generalisation of women in art, welcomed the female artist as a cultural norm, and the shift from gender discrimination has evolved into a celebration of female artistic achievement.

But art history, laced with the female ideal and its associated biases, provides an interesting insight into the objectification of women and their central role in art from the very early age of human civilisation, and one which can now be celebrated with impartiality.