Richard Hemery is a history enthusiast and avid collector of things. You can follow his photograph collection at @victorian_fashion_photos and his mudlarking finds at @thames_pottery.

Tell us about how you began collecting Victorian photographs.

Because I come from a Jersey family, I inherited a part of the family photo archive. One day I went to a well-known local auction site to see if I could find more, and I ended up with 1.000 photographs from Jersey! I’ve always been a bit of a hoarder and collector, and that’s how it began.

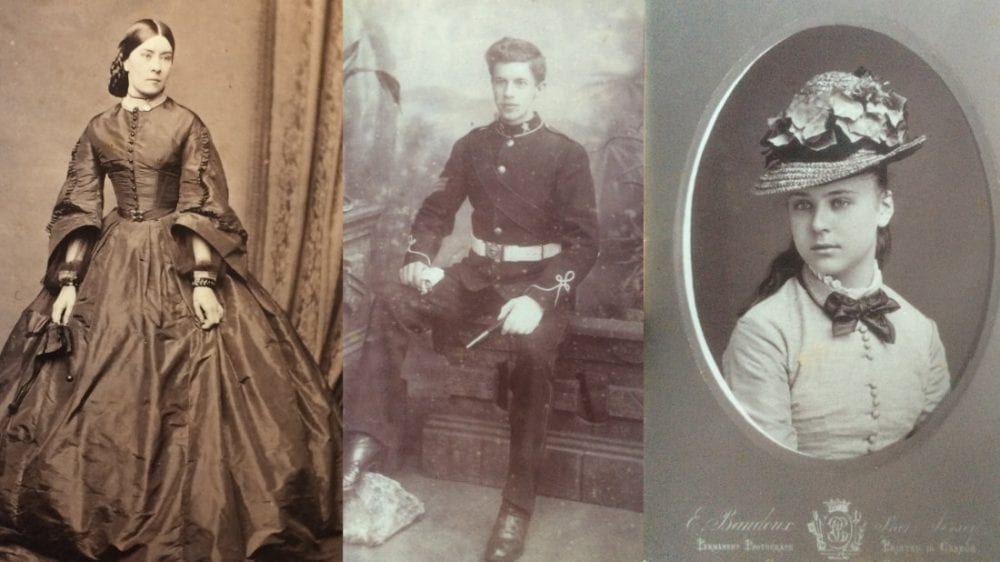

Richard Hemery’s Great Great Grandparents in the 1860s

So your family is from Jersey, but you don’t currently live there?

That’s right. My great-grandfather was one of the many people who moved off the island in Victorian times when work was difficult. I’ve been back several times, and I’ve got a couple of distant cousins who still live on the island.

Tell me about how you built your collection and what criteria you look for when adding to it.

I’m very broad in my collecting interests. I cut off at the start of the Second World War, so it’s mainly Victorian and a few Edwardian. Otherwise, I’m open to any photos, any condition. You can buy whole albums, so I’ve managed to acquire large groups. Some photographs are named, although that’s very rare. Most Victorian photographs are unidentified, with no name written on the back. 99% of the ones I have are of unknown people. I love the images: that moment in time, the changing fashions, the way they dress their children, and the men’s hairstyles. With these details, you can narrow down the dates quite accurately.

I have a browse through online auctions and see if there are any interesting ones. Obviously, the more interesting ones tend to go for quite a lot of money. I’ve got such a large collection, and I don’t need to add to it hugely. I think my wife would pull her hair out if I added another 1.000!

Can you identify different photographers’ works and the time period?

You can. Sometimes, the back of the cards is just as interesting as the front. At the time, nobody could afford to have their own camera. If you wanted your photograph taken, you went to a studio. From the late 1850s, they developed a cheap method of mass-producing and copying photographs. So you went to your studio in your Sunday best, had a dozen photos copied, and gave them out to your friends. Using the almanacs, illustrations and newspapers of the day, you can pretty easily date when the studio was open and then the dates the photographer was active. Even a small town like Saint Helier would have had fifteen or twenty photographers. It was a big business in Victorian times.

It’s very rare to find photographs that show any expressions, people wearing their working clothes, or animals. In my 1.000 photographs, I only have one Jersey cat and one Jersey dog. Right through to the 1870s, you had to pose for several seconds, which is why they look so stiff and formal. After that, it was pretty much an instantaneous process, and you could also pose outdoors.

Do people ask you questions about the fashion specifically?

Sometimes. Normally I get questions from people who are looking for the specific name for the item of clothing. It’s great that you can follow the fashion right through — from these wonderful hoop skirts and crinolines to the less formal styles of the 1870s and then to 1910 when you’re getting a much more modern look.

I’ve always been interested in history, and fashion has something of a universal appeal. For most people, it’s how the person looks and what they’re wearing that is attention-grabbing, rather than that they come from the Channel Islands.

I believe you are also a keen mudlarker? How did you get into it?

I am an archaeology graduate, so I’ve always been into history. I read a book about someone who walked along the Thames foreshore picking up historical artefacts, so I thought, “Oh, I’ll have a go at that!”.

London is where I go mainly because the tide goes out a long way on the Thames, and much of the foreshore is exposed. Obviously, you’ve got the 2000-year history of London right there. Mostly I look for pottery, and I’ve found Roman, medieval and post-medieval items. I’ve actually written a book about how to find and identify pottery on the Thames foreshore.

There’s a whole group of people who do it in Jersey. They have a Facebook page, and there’s plenty of older stuff to be picked up there as well. The pottery fragments tend to be much smaller because they’ve been rolling around in the waves, but you do have interesting places like the submerged forest. Recently someone found a bronze age spearhead in Jersey, which was preserved among the peat and the tree stumps of the forest when the sea levels started to rise. There are some great finds to be had there.

How do you decide when and where to go?

It’s mostly to do with the tides. When you have a full moon, you have a shallow tide and then a very high tide. Because I don’t live in London, I tend to pick a shallow tide, so I have time to walk for miles and miles. I mainly look for pottery, but other people look for coins, pins, buttons, and a whole wealth of artefacts. Part of the fun is the research to identify your finds afterwards.

I tend to go to the city because that’s the core of London’s Roman and medieval city. You get the older finds there, but you can walk right out into the estuary and find many different things. Different areas have different periods of finds.

There was a container of Lego that fell off a ship in 1997. So now you find bits of Lego on the beach in the southwest of the Channel Islands; there are five or six different models that keep turning up.

While I’ve been in lockdown, I’ve been spending far too much time online. When I find a small piece of pot on the Thames, I’ll look for the full thing online; and then I’ll buy it if it’s not too expensive. Our garage is full of boxes of pottery sorted by age and type, and I’ve got some of the best bits in a glass-topped table.

If the finds are of archaeological or historical interest, you can register your finds on the Portable Antiquities Scheme, where people can study them. There’s the law of treasure trove, which says if your item is more than 300 years old or made of precious metal, you must declare it. Museums have the option to buy it, but they have to pay you the full market price. With pottery, that hardly ever happens; most museums are chock full of bits of pots they’ve dug up, and they certainly don’t want any more.