…fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners. Often the attachment is scarcely perceptible […] But when the web is pulled askew, hooked up at the edge, torn in the middle, one remembers that these webs are not spun in mid-air by incorporeal creatures, but are the work of suffering human beings, and are attached to grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in.

Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

Taking up space can feel uncomfortable.

During the search for the right nooks and crannies to anchor our imaginative spider webs, it’s easy to settle for less than you and your work deserve.

When first confronted with ‘working from home’, I tried to balance my laptop, notebooks and mug of tea on a much-too-small, much-too-cheap fold-out desk so that, come the end of the day, my workstation could be eviscerated just as quickly as it was established. Out of sight, out of mind. As my posture worsened, so too did my productivity and it gradually dawned on me that my invisible desk tactics weren’t nifty space saving measures worthy of a peppy interior design series on Netflix, it was another attempt to shrink myself and my work down so small that it was virtually undetectable in my own home.

Virginia Woolf’s Legacy

In Virginia Woolf’s essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’, she argues that the historic restriction and policing of women’s private lives, alone time and financial independence is responsible for the inequality between male and female writers – both in terms of who gets published and whose work gets celebrated. As an example, Woolf explains that Jane Austen “would have to write in the common-sitting room… to the end of her days” and would conceal her manuscripts from others by “cover[ing] them with a piece of blotting paper.”

So, my behaviour had a pretty prestigious legacy then… I didn’t know whether to be comforted or unsettled.

For Woolf, financial security and “a room with a lock on the door” are the essential ingredients for women’s creative success. Whilst Woolf’s essay focuses on the uneven landscape between male and female writers, I wondered what light her words would shed on how visual artists in Jersey can take up space.

What exactly does it mean to have a room of one’s own today?

I caught up with some local artists – Pippa Barrow, Michelle Le Cornu, Elīza Anna Reine and Lisa Scholefield – who all have their own studios, to talk about what it means to them and what they wish they knew when they were first looking for a space to call their own.

First of all, I was curious to find out whether taking the leap into having a studio space was a tricky decision for any of them.

Collage and mixed media artist Elīza said that whilst she “couldn’t imagine life without a studio space now,” she didn’t always feel that way.

I used to think having a studio space was a waste of money if you can work from home, and only full-time artists have them. Silly me. Little did I know that it would be the studio space that made me one too.

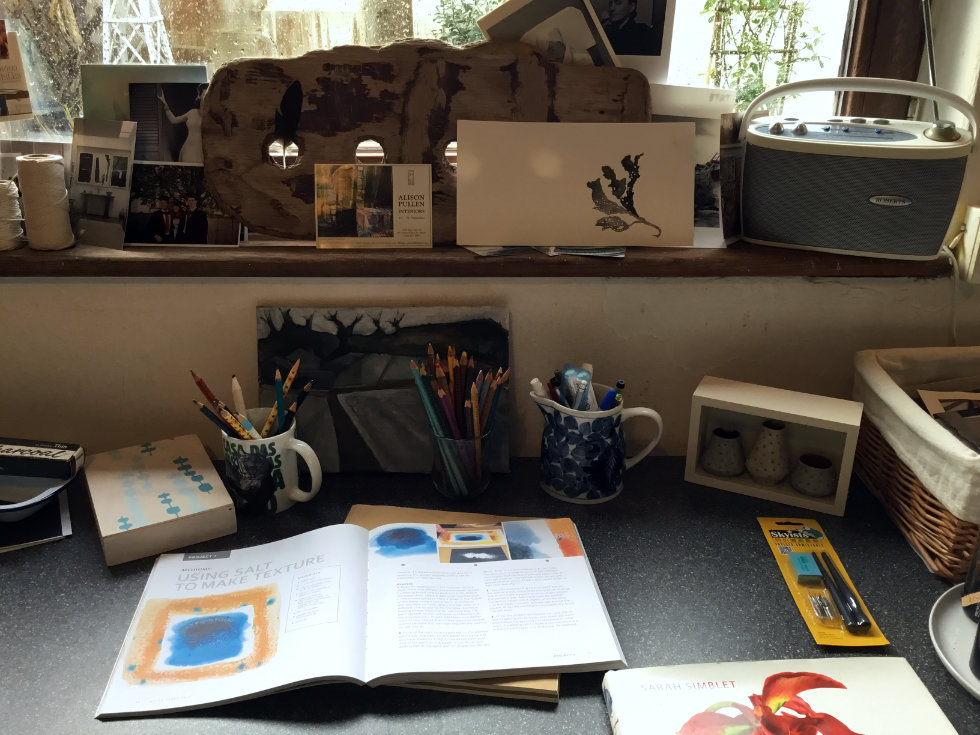

Lisa, who trained in ceramics and has an interior design background, now uses her new garden studio for making her own inks and dyes from foraged materials which she is using to paint the landscapes she sourced them from.

She admitted she “suffered badly” from what she described as “studio envy” for many years before becoming “the proud owner of a garden studio” this summer. Lisa described the move as “the step up” she needed in her creativity and that it “is symbolic of taking [her] work seriously.”

Sculptor and ceramicist Pippa echoes this sentiment, commenting:

I’ve found throughout my life that having a dedicated space for making work is really essential; especially as a woman working in the arts, and particularly in Jersey, where art is seen as not really working at all. Being able to focus on what you do [and] allowing yourself to take your practice seriously is vital.

She explains that finding her ArtHouse Jersey-run studio on the French Harbour 12 years ago was “literally life-saving” for her.

I was very depressed after leaving my previous job at the height of the 2008 financial crash; I couldn’t even find a part-time job and was not in a good place. I’ve been a maker most of my life, so having a space I could create in that was affordable, allowed me to take the first steps towards becoming self-employed.

Read Part II to find out how having a room to yourself is crucial to the creative process and how to find yourself a studio in an island like Jersey.